Blog Archives

For Love of Hummers

It has been over two years since I last posted a blog. I’m not sure why I lost interest in blogging, and I’m not sure why I’m back again, but perhaps that doesn’t matter anyway. I am here because I have an urge to write and post some photos. It is going to be light this time, nothing deep or philosophical, and I figure what better way to start than to blog about hummingbirds.

We have two regular species of hummingbirds here on Vancouver Island, the Rufous and the Anna’s, and it is warm enough in the winter that the Anna’s overwinters as long as there are hummingbird feeders to help them out. Even though I live in a townhouse with a very small backyard, I regularly get Anna’s Hummingbirds through the winter, and the Rufous visit the yard during both spring and fall migration. This year for the first time since I moved here seven years ago I have had Anna’s coming to the feeder all summer long. So here are some photos of these birds from both last year and this, with some comments about them.

I found this little beauty last year in a friend’s front yard right beside the driveway. It is a female Rufous Hummingbird, and the delicate little nest is made of lichens and spider silk. Because she was so close to the driveway, she was quite tolerant of human presence. At this point she was sitting on eggs

Five days later and the eggs had hatched and the young were already a fair size. Here you can see one of the young begging for food.

Here mama is feeding one of the young, an act that any sword swallower could learn from. Although there were two young it was clear that one was the dominant bird and was getting the lions share of the food. Only one bird successfully fledged and we later found the other young dead in the nest. This is a common strategy amongst birds as it allows both young to survive when food is plentiful and still ensures that one will most likely make it when food is not so plentiful.

I had at least three Anna’s visiting my feeder this past winter. This is a subadult male showing rather distinctive plumage

The same hummer stretches it’s wing while guarding the feeder. This was the dominant bird at the feeder all winter long, and would often perch on a branch of the lilac bush that is right beside the feeder

This is a different male Anna’s guarding it’s chosen territory early in the spring. It is in the process of repositioning itself on the perch, hence the body contortion. As tiny as they are, hummingbirds can be ferocious birds, chasing away much bigger birds than themselves if they are perceived to be a potential threat.

My friend Carla has a wonderful backyard for hummingbirds, which she allows me to use for my photography. In fact the first image at the beginning of this blog is a female Rufous Hummer at a fuschia taken in her yard. Here a male Rufous hovers in front of me, giving me the once over.

Still in Carla’s backyard, this female Rufous hovers in front of Crocosmia looking for a drink.

What are you doing? You get at the nectar from the other side! Actually, we figure that this female Rufous is picking off tiny insects from the backside of the Crocosmia.

Even birds get itchy and have to scratch. This is a young Anna’s in my backyard taken this summer. Her throat feathers are matted and I suspect that it might just be the sugar water from the feeder. Even young birds can be messy eaters.

This male has dominated my feeder all summer long, terrorizing any other hummer that tries to get a drink when he is around. I have to wonder if it is the same male from last winter. I just love the variety of colours in his gorget.

I absolutely love hummingbirds. They are amazing jewels with an attitude and ferociousness that belies their diminutive size. But they are descendants of the dinosaurs so maybe that’s where it comes from.

If you want to see more of my photos, including many species of hummingbirds from Costa Rica, please visit my website at :terrythormin.smugmug.com/

Vancouver Island Dragonflies, 2012 season – Terry Thormin

It has turned cool here, cooler and cloudier than normal, and it feels like fall. Dragonfly populations are noticeably on the decline and many species have disappeared altogether. So I have decided that it is time to wrap up the season with a blog.

This year was a mixture of good and bad when it comes to dragonflies, and I will give you the good first. I managed to see five new species for the island and I managed to photograph four new species and get a few species in flight that I had struggled with before.

Forty-one species of dragonflies have been recorded for Vancouver Island, and my hope is to eventually see and photograph all of them. The main reason that I did so well this year is that I finally found a bog at higher elevation. The bog is part way up the road to Mt. Washington at an elevation of 2620 feet, and is aptly named 9 km Bog. Here, with the help of two good friends who are as crazy as I am about dragonflies, we managed to find Hudsonian Whiteface, Crimson-ringed Whiteface, Sedge Darner and Ringed Emerald and all four were new for us on the island. It was easy for us to photograph the Whitefaces as they regularly perched on the vegetation, but the darner was more of a challenge as we had to get it in flight, but all three of us succeeded. The emerald was the tough one as it rarely hovered for more than a couple of seconds and was very hard to find perched. This one I did not get although I have a perched shot from Alberta.

On one of my trips to Bowser Bog, a bog at low elevations that has recorded 26 species of dragonflies, I finally managed to get photographs of a perched Saffron-winged Meadowhawk. Of course, a few days later I photographed one in flight at Little River Pond. This was the first record for that species at Little River Pond, putting the total for the pond up to 21 species.

My final good dragonfly was a Black Saddlebags at Rascals Pond in Parksville. Black Saddlebags is a dragonfly that is recorded only sporadically for Vancouver Island. I do not have all the records, but I know that it has been a few years since one has been seen on the island. This is a known migrant, and it is probable that our records are all of migrants from the south. Considering how few active dragonfly watchers there are here, this species could be much more common than the records indicate. There were at least three individuals at Rascals Pond, two males and a female that I observed ovipositing. As well there was at least one other individual at another pond in Parksville. I went to Rascals Ponds three times and saw the Black Saddlebags on all three occasions, but because they were always in flight I was unsuccessful in getting any photographs.

As for those in-flight shots, I mentioned two of them, the Blue Dasher and the Four-spotted Skimmer, in an earlier blog, “Photographing Dragonflies In Flight”, but at that time I had not succeeded in getting a good in-flight shot of a Common Green Darner. Well I finally did and, as is so often the case, I have since then managed to get a few more good shots. So here is one of them.

And to top it off, I also managed to get my first in-flight shot of a Striped Meadowhawk, another species I had tried for without success on previous occasions.

I have managed to see 26 species of dragonflies so far this year, and succeeded in getting lots of photographs, so what is the downside? The answer can be summed up in one word, numbers. The darners in general seem to be down in numbers somewhat, although not dramatically. The skimmers and meadowhawks though seem to be drastically down, at least in locations that I am familiar with. Meadowhawks that we were seeing in large numbers at Bowser Bog last year we were only getting ones and twos of this year. The numbers of Common Whitetails, Four-spotted Skimmers and Eight-spotted Skimmers at Little River Pond seemed to be down this year and I saw very few Dot-tailed Whitefaces and not a single Western Pondhawk. The meadowhawks in general were well down in numbers. In fact, the Autumn Meadowhawk, which is our last dragonfly to appear, generally emerging in numbers in mid August, has not put in an appearance this year at all so far. I spent two hours at Little River Pond today where it is usually common by now, and although I did see five other species of dragonflies, there was not a single Autumn Meadowhawk to be seen.Just so you know what this dragonfly looks like, here is a photo of an Autumn Meadowhawk taken last year.

The only dragonfly that I can say has been truly here in good numbers is the Common Green Darner. In fact I don’t recall them being this numerous at Little River Pond before. The interesting thing though is that, like the Black Saddlebags, this is a migratory dragonfly. It would be hard, maybe impossible, to determine what percentage of our population is made up of migratory individuals, as there is a resident population as well, but it is quite likely that the large numbers of this species this year are accounted for mostly by migrants.

I have been concerned about insect populations on the island ever since I moved here three years ago, and other people who have lived here much longer than I have expressed the same concern. But dragonfly populations seemed to be the exception, that is, until this year. Because dragonfly larvae can live for several years before emerging as adults, this might just be the reason why they were not showing a population decline until now. It is interesting that the meadowhawks are showing the biggest decline in numbers, and these are the smaller dragonflies and the ones that generally spend the least amount of time in the larval stage. This decline in dragonfly numbers is very worrisome, and it will be interesting to see if it continues next year. I believe that this island needs a wakeup call, but I am not sure what it will take to do it. Unfortunately most people pay so little attention to insects that they will never notice declines in populations, and if they do I am not sure they will recognize the significance.

When I wrote an earlier blog “A Passion For Dragonflies” I included a poem. When I wrote that poem, in a frenzy of creativity I wrote another, free verse version of the poem, which I did not include with the blog. Somehow that poem seems appropriate now, so here it is.

Dragonfly

It courses over the pond

on wings flashing in the sun.

Colours of red, blue, green and yellow,

colours of the rainbow,

and black and white for contrast.

It hunts for food,

for a mate,

for the next generation.

Always keeping an eye out for danger,

from above and below.

But the real danger it does not see,

the danger from humans.

draining wetlands,

using pesticides,

herbicides.

A danger that kills all,

indiscriminately.

But its loss is our gain.

Or is it?

For if we lose the dragonflies

do we not lose part of our humanity?

Part of our souls?

Part of the soul of our planet?

Is it not better to protect the dragonflies?

To watch, to really see them?

They can bring joy,

peace,

tranquility.

If only we all could become

“Watchers at the pond”.

© Terry Thormin, August 2012.

Hunters in the Pond Part 2 – Terry Thormin

The dragonfly patrols the south shore of the pond, searching for a mate. It is the largest of the dragonflies in the pond, a Common Green Darner, and so pays little attention to the other dragonflies even when the diminutive Blue Dasher comes darting out at it in an effort to protect its territory. From the top of a pine tree at the east end of the pond a Merlin surveys the pond, waiting for the right moment. There are several Common Green Darners flying and surely one will be careless this time. Now! It launches itself from the pine and plummets down, picking up speed until it levels out low over the water. Distracted by the dasher, the darner doesn’t see the Merlin until it is almost too late. Frantically it twists and picks up speed, but the Merlin is too close and rakes its left side, almost tearing both wings off. The Merlin continues down the pond without its prey, but the darner, badly injured, spirals to the water’s surface where it flaps in a futile effort to take flight.

The rippling water sends out a circle of vibrations and very quickly a water strider responds, skating across the water’s surface towards the injured dragonfly. It approaches and when the struggles subside it moves in. The initial jab from its needle-like mouthparts starts the dragonfly struggling again and the strider quickly backs away. A few minutes later the struggles quiet down again as the life energies seep from the body of the dragonfly. Again the strider moves in and pierces the dragonfly’s body with its mouthparts. Now the dragonfly is only struggling weakly and the strider persists, sending digestive enzymes into the dragonfly and sucking up the resulting dissolved fluids. Within a few minutes there are four striders feeding on the dragonfly, then five and finally six. Two species share the dragonfly carcass. There are three larger water striders, wingless even as adults, and three smaller ones, all with wings. Within a couple of hours the water striders have abandoned the darner’s body and there is little left but an empty husk. Even then a couple of snails move in, gleaning whatever is left. Nothing goes to waste in the pond.

I did not actually observe this event, it is fictional, but one that could easily happen. I have observed water striders feeding on other insects trapped on the surface of the water, and just recently photographed a group of water striders feeding on a dragonfly, in this case a Hudsonian Whiteface.

Water striders are both predators and scavengers, feeding on any insect that falls onto the surface of the water. They are also known as pond skaters and Jesus bugs because of their ability to walk on the surface of the water. They are found on quiet water like marshy lake edges ponds, marshes and backwaters of rivers and creeks. They do not like fast flowing water. There is one exception to this though, and quite a remarkable exception. Water striders in the genus Halobates are the most marine of all insects. While most of the 46 species in this genus are found in coastal areas, 7 species are truly marine in distribution and can be found hundreds of miles from any land. Unlike other members of the genus, and other water striders, these 7 species feed on plankton.

Water striders are true bugs and as such they do not go through complete metamorphosis. Instead the young water striders look very similar to the adults, just smaller and without wings. The young, like the adults, live strictly on the surface of the water. There are about 750 species worldwide, the largest getting up to more than 36 mm in length.

There is another pond insect that deserves attention, the water scorpion. It is not a true scorpion, but rather an insect, and is a true bug just like the water strider. Unlike the water strider though, it spends most of its time below the surface of the water. It is an air breather though, and has to come to the surface to breath. Water Scorpions, however, have breathing tubes at the back end that are often almost as long as the body. For this reason they are often found sitting on vegetation below the surface with just the tip of the breathing tube sticking out of the water.

Water scorpions are ambush predators that look like aquatic walking sticks, but with front legs that look more like those of a praying mantis. Some species though are much broader through the body and look something like a skinny giant water bug.

Earlier this summer I observed a rather interesting episode with a pair of damselflies and a water scorpion. As usual I was sitting in my camp chair beside Little River Pond waiting for opportunities to photograph dragonflies when I noticed some activity in the water right at my feet. It was a female damselfly below the surface of the water. Female damselflies will often go completely underwater to lay eggs and the theory is that by so doing they will not be harassed by other males attempting to mate with them. Usually they remain attached to the male they mated with, but on this occasion she was by herself and she seemed to be struggling to climb to the surface on an emergent plant stem. I looked more carefully and noticed a water scorpion that had grabbed her by the wings. Most likely while she was ovipositing she got too close to the water scorpion which made a grab for her and only got the wings.

With great effort she managed to drag herself partly out of the water. Then a male flew in, most likely the one she had mated with, and grabbed her with his appendages by the front of the thorax. Anyone who is familiar with dragonflies and damselflies will recognize this as the tandem position. Between the two of them they managed to eventually drag the water scorpion completely out of the water. Shortly after the female was clear of the water the water scorpion dropped back into the water, either having let go or perhaps tearing through the wings of the female damselflies, and the damselflies flew away. That the male came to “help” her I seriously doubt, but my guess is that the female would not have made it without his help.

Water scorpions range in size up to about 44 mm not including the breathing tube. There are about 270 species distributed worldwide. All are ambush predators and will feed on things up to the size of tadpoles and small fish. They are found in quiet, shallow lakeshores, ponds and slow moving streams.

There are many other predators found in ponds, marshes, lakes, streams and other freshwater habitats, and perhaps at sometime in the future I will write about some of them. Anyone who takes time to sit, and observe at the edge of a pond will undoubtedly see and learn something about many of these fascinating creatures. Unfortunately, most of us leave our fascination with pond life behind when we reach out teens. I think that this is unfortunate as it is an amazing habitat with many amazing creatures, and one that is a good indicator of the health of the planet.

The Not So Common Green Darner – Terry Thormin

Although the day started out on the cool side, as the clouds cleared it gradually warmed up nicely, warm enough to make me think about going out to Little River Pond in the afternoon. There is one photo that, after almost three summers of trying, I still have not been able to get, a shot of the Common Green Darner in flight. Oh, I have come close. I have taken some fuzzy, out-of-focus shots, and I have, on several occasions, almost managed to get the shot. What makes this all the more frustrating is that my cousin Mike had managed to get at least two good in-flight photos of this dragonfly on his very first visit to the pond.

So once again I found myself sitting in my camp chair at the edge of the pond, following the dragonflies as they patrolled the edge of the pond looking for mates, and hoping that a Common Green Darner would hover long enough for just one shot. Well, I never did get my photo, but I did see something that I have never seen before. There was lots of mating and ovipositing going on, and I am always interested in improving my shots of the darners ovipositing. Just in case you are not sure, ovipositing means egg-laying.

When dragonflies mate they do so in the wheel position. The male uses the appendages at the tip of his abdomen to grab the female at the back of the head and the female then curls her abdomen under her thorax and makes contact with the second segment of his abdomen where he has deposited his sperm. This forms an irregularly shaped wheel. I have never been able to find perched Common Green Darners in the wheel positon, but here is a photo of a pair of California Darners in this position.

When the female is ready to lay eggs, she disconnects her abdomen from the male’s abdomen. At this point the technique used by the female for egg laying varies depending on the group of dragonflies. In the case of the Common Green Darner, the male continues to grab the female at the back of the head, and they fly in tandem like this from floating vegetation to floating vegetation.

They will land on anything that has a submerged stem and the female will proceed to probe the stem underwater with the tip of her abdomen. She will then make a slit in the stem with her ovipositor and insert a single egg. At times she will reach so far down the stem of the plant that her whole abdomen and part of her thorax are under water. She will do this over and over again, laying several eggs in one stem and then moving on, with the male still in tandem, to another plant to lay more eggs.

During this procedure it is not uncommon for another dragonfly to hover over the ovipositing pair. This is sometimes a male of a different species, but often another male Common Green. I have at times seen male Common Green Darners actually dip down and “attack” the male that is in tandem with the female. The theory is that the male stays in tandem with the female to ensure that she does not mate with another male before laying eggs. This attack then might be an attempt on the part of the single male to dislodge the male in tandem. I have never photographed a lone male Common Green Darner attacking or hovering over a mating pair, but this photo shows a male Blue-eyed Darner hovering over a pair of Common Greens.

On this occasion, as I was watching a pair in the process of ovipositing, a lone male flew in and landed right on the back of the female. It then looked as if he reached forward and bit the other male right near the tip of his abdomen. This caused the male in tandem to immediately lose his grip and fly forward a short distance. What happened next was so quick I almost didn’t catch it all. The interloper reached forward with the tip of his abdomen, grabbed the female on the back of the head with his appendages, and took off like an arrow with the female in tow.

The other male, in the meantime, circled around and came back to the spot where the female had been laying eggs and circled around, legs dangling down, apparently looking for his mate. After circling around for about 30 seconds he flew away, but then came back a short time afterwards and did the same thing again before finally flying away for good.

I have never seen this behavior before, and have never read about it anywhere. I am curious to know if it is something that has been observed by other people. Unfortunately it all happened so quickly that I was unable to get photos. Like everything else in nature behavior evolves and perhaps this is a newly evolving behavior in Common Green Darners.

The Second Flight of the Margined White – Annie Pang

“I don’t think we should go” I muttered over and over, but John was indifferent to the potential waste of time and precious little energy I had as well as the depression that had come with my ongoing disappointments. He silently kept packing the few supplies we would need and so did I as I paced back and forth putting stuff by the door. On this day, I felt like a piece of walking bad luck. The butterfly season had been alarming in so many ways. It wasn’t just the lack of butterfly numbers in Victoria, but my entire world, it seemed, had gone missing and in its place had come only chaos and bewilderment.

If you recall, the last time we had been to Cowichan Station I had spotted a single Margined White butterfly during the last of its spring flight and I couldn’t see, with butterfly numbers so low this year, how I had possibly let myself miss my records of previous years’ dates, when I had done my trips in July for the summer flight of this species. I was late, but then everything was late this year, so why was I so resistant to going? The butterfly was calling to me again, but I was only hearing the fear inside. Time had passed quickly this last month and now John insisted we go even if I was feeling agoraphobic.

Once again I found myself traversing the Island Highway, John driving as I spun wool in my lap almost mechanically until I realized I was missing the beautiful vista of the scenery driving over the Malahat. I wish I had taken a picture or maybe several, but I don’t think anything could have done it justice. Gone was my tiny little world of troubles, opened up by the vast expanse of forest, sky, mountainside and waters, far below us, as we climbed higher and higher away from the city.

But the day was hot, too hot for me and I remained overly worried that the butterflies would not be there. It was a forty minute drive to Cowichan Station, maybe longer, and by the time we arrived there the heat had become suffocating. No butterfly would be landing to sun in this. I hadn’t wanted to make this trip just to see them because that was never enough. My camera was hungry.

Things seemed different from the previous month as we parked by the old building. The angle of the sun had changed a great deal. Vegetation had grown dense and tall, was bearing fruit or flower. There were lots of daisies in bloom as well as yellow, dandelion-like flowers. The hogweed had finished flowering and was going to seed making it seem later than last year, maybe too late. We walked along the rails anyhow as we had come all this way and had nothing to lose. There was no sign of life that belonged to any butterfly though plenty of honey bee-laden thistles so we kept trekking along the tracks and I took pictures of one thing or another out of frustration, while the sun pounded down on me.

While I passed a few patches of Herb-Robert I still saw no butterflies. Time passed – we took solace in the cooling shade of trees and ferny areas and finally came around a curve, into a sunny glen beyond a tunnel of Big-Leaf Maples…..and there they were, like summer snowflakes flying up and down, back and forth – at least 10 or more just in that sun-bathed spot, sometimes landing on Herb-Robert to nectar but not very often and certainly not long enough for me! I could tell this wasn’t going to be an easy time with the temperatures so warm.

Obsessed with getting any pictures at all, I moved in as one butterfly landed beneath some vegetation and took a number of very poor shots that were out of focus and in poor light. I gave up and let them have their summery flights of fancy, which were more likely for territory and mating rituals. We decided to walk further and return later because this was their turf and they weren’t going anywhere else.

Up ahead, in another sunlight clearing we spotted a second horde of Margined Whites, and as we slowly crept up I found one that was hungry and wanted to land, and then another and another! Engrossed, I got one in the sun, its wings an opaque-white with an almost greenish tinge as it nectared on Herb-Robert. Then it was off, but I’d gotten my first decent shots and was feeling better, much better.

Suddenly there was a flurry of activity in front of me. A female had landed on a long, wide blade of vegetation and there was a very persistent male butterfly wanting to mate with her. What luck for me! They might mate or she might choose another but either way, at least for the moment, she didn’t seem to want to budge. I saw her raise her abdomen, her way of rejecting his advances, yet as he persisted I had the opportunity to get fairly close and take a number of shots of her in the oh-too-bright sun.

Happy me! But eventually, another male approached and then another and suddenly they were all spiraling in a furious, white flurry …

Up, up, to the brilliant sky.

“Bye, bye, butterfly…”

I was pooped. We had walked a long way and I was all for heading back.

As we passed the large leaves of Thimbleberry bushes, a flash of swirling orange flew up to the side. I swear it was the same area as in previous years where I’d seen at least one Satyr Comma and this was no exception except that there were two of them. Only one landed but in the heat, there were only side shots to be had for the butterflies had no need to sun with opened wings. I took the best ones I could although the angles were awkward. And then, I saw a lovely little dragonfly and at first thought it was another female damselfly, but it wasn’t. It was some sort of spreadwing. I took the best shots I could, but the lighting for this camera was either too harshly overexposed or too dim and it simply did not want to focus on the spreadwing very well. This was my very first sighting of one and so, once again I became very frustrated. But the shots were good enough for a small peek at what I saw; a young female Emerald Spreadwing! My thanks to Terry and Rob Cannings for helping to identify it. I have only given you a small glimpse below with the following picture of the Satyr Comma. When it is older it will look more like Terry’s most excellent picture of a mature female Emerald Spreadwing which he most generously offered to let me use.

I also spotted a number of European Skippers that had not been in evidence only an hour earlier. I had never seen them in this area before, but as Cowichan Valley was covered in rural farmland and these skippers seemed to travel with the transport or presence of Timothy hay, I’ve since learned, it wasn’t all that surprising to see them here.

The day grew older.

Back at the initial clearing where we’d seen the first cluster of Whites, I spotted one that was flying low as if looking for a place to land, always a promising sign for getting pictures. It finally did alight in a shady spot by the rails to nectar on yet more Herb-Robert, which seems to be the Margined White’s favorite flavor of flower that I’ve noticed here. I pretty much had to lie down on the tracks but I got my shots and it was fascinating to me how the light played with the images of this creature, now making it translucent. I could see its body and spirit through its wings in these shots, both magical and nymph-like. At the end of my tale I will leave you with a double sonnet and the best image I was able to get lying there in the peace and heat of the abandoned rails.

I can’t explain to you why these butterflies are more beautiful to my eye than the Cabbage White. Is it because they are less plentiful in general and not found at all down in Victoria? Is it because I must come this far to find them? Perhaps so, or perhaps it is because they are a butterfly of this land, because they belong here and they have their territories that I know about. Perhaps it is because they give me hope by their reliable continuance….at least for now. This place has not been altered or disturbed recently and there is no development going on. The tracks have been deserted for years, although when the train came along in previous years, it never bothered these Margined Whites though we’d had to scramble up the side of a slight rising next to the tracks as the train came whistling around the corner to whoosh by, only a few meters from our noses. I looked over my shoulder at the sad and ghostly image of the overgrown railroad as we went back to the van, and a part of me hoped that the train would someday return so that others might once again travel through this lovely place, this lovely land where snowflakes fly in summer, and once again they could marvel at all this beauty. Maybe it would help us stop to look at what we all have to lose if we keep disturbing the habitat of our lovely bit of nature that is left.

And I don’t think the butterflies would mind the odd passing of an old friend, be it a train or someone seeking hope…with a camera…

Return of the Margined White

I promised you, remember? They’d return

and bathe their wings in Summer’s golden light,

but you must walk the rails amidst the fern

while watching for my children’s drifting flight.

Like purest snowflakes, floating ‘round the bend,

you’ll see them settle on a bloom to feed

and what a dance amongst them you will spend,

and how much patience you, my dear, will need.

For they care not how far you came to see them,

their lives too short for them to want to waste.

You’d know things wiser if you tried to be them

and then, perhaps, more wisdom would you taste.

You’ll hear their call and, if you’re quiet and still,

they’ll let you and your camera drink your fill…

You see, my dear, behold the summer flight

returning as I told you that we would,

our wings still margined but of lovely white

and I would be there like this if I could.

We butterflies are only here so long

before our time is over and we’re gone

so heed our calling, listen to our song

that you have always so depended on.

Then we will land because we see you here

and we will tease you – lead you here and there

until you’ve lost your worries and your fear,

until you left behind your every care.

And landing on a tiny bloom to feed,

we let you seize this time with us you need…

© Annie Pang July 2012

A Whitetail Tale – Terry Thormin

Today I want to tell you the story of the Common Whitetail. I am not talking about the Whitetail Deer, but rather the dragonfly. This is a rather attractive dragonfly, with a dark chocolate head and thorax, a chalky white abdomen and large, dark chocolate patches on all four wings. It is a fast flier that seldom hovers, and when it does it is only for the briefest of time, making it very difficult to photograph in flight. Most of the time it perches on the ground or on a lily pad, not making for the best of perches when one is trying to photograph it. And therein lays the first part of my tale.

I spent 3 ½ hours at Little River Pond six days ago with two of my photography buddies, my cousin Mike Wooding and Tim Zurowski, both very fine photographers. As it turned out, Mike did not have photographs of the Common Whitetail, so we spent a fair bit of time trying to get good photos. There was a relatively bare patch of ground right next to the pond where one of the Whitetails was regularly perching, and Mike and I started off taking photos of it that way. Knowing the behavior of this dragonfly, I found a dead twig and pushed it into the ground at about a 45 degree angle to horizontal. I have often see Whitetails perch on vegetation that angles like this as long as they can perch fairly low.

Sure enough our Whitetail soon came in and perched low down on the stick. Mike took several photos, but was not entirely happy with the background as he was shooting down somewhat on the dragonfly and the background was too close to the stick. So he got the piece of carpet I keep in my car just for this purpose and put it on the ground at a suitable distance from the stick, then lay down on it to get a better angle and waited for the Whitetail to return.

And waited, and waited……

Until finally it flew in and landed……on his back……

Now even the world’s best contortionist would not have been able to get that shot, but of course I had my camera and I managed to immortalize the moment, that is, after I was able to stop laughing.

Eventually the whitetail did land on the stick and Mike was able to get his photographs. Just so you know how effective the effort was, here is my photo taken from the same spot later on.

I went out to the pond again the following day and very quickly the Whitetails promised to entertain again. There were two males that were constantly squabbling with one another. One had staked out a territory right in front of me and was using the stick from yesterday as its perch. Whenever the other one would come cruising by too close, the one on the perch would take chase and the two would dash across the pond, one in hot pursuit of the other. Eventually a third and then a fourth male put in an appearance and the dog fights became more frequent. The intensity skyrocketed though, when a female put in an appearance. I first noticed her trying to oviposit in the water close to shore.

Female Whitetails oviposit by flying just above the surface of the water, dipping down to touch the tip of their abdomen in the water and laying the eggs one by one. The eggs then drop to the bottom of the pond where, if nothing eats them, they will eventually hatch. During this time the females are usually fairly easy to photograph.

At the same time the male is often flying above the female, protecting his sperm investment from other males. During this time he will sometimes hover just long enough to make photography possible, so I am always on the lookout for this sort of behavior.

This time though, with four males in the area, the level of activity became so fast and furious that photography became impossible. At times there were three males around the female, and often there would be a tight ball of flying dragonflies, twisting and turning like a tornado. At one time when two males were competing for the female their flight became so intense that they rose from the surface of the pond in a tight ball and flew erratically in my direction. Two of them flew past me with inches to spare and one crashed directly into my chest, recovered and then took up the chase again.

Obviously we humans are not the only creatures who let our hormones get the better of us. The sex drive is a powerful thing, and, when you think of it, essential to the continuation of the species. But I have to wonder how many dragonflies never get a chance to mate because they are blinded by the chase and never see the Merlin in plain view.

I thought I would leave you with this photo of a Common Whitetail and a Cardinal Meadowhawk sharing the same perch, something that I suspect two Whitetails would never do.

And if you are interested in seeing more great dragonfly photographs here are links to three galleries:

Tim Zurowski Photography:

http://www.zuropak.com/dragons.htm

Mike Wooding Nature Photography

http://nahanni.smugmug.com/Dragonflies

Terry Thormin’s Nature Photographs

http://terrythormin.smugmug.com/InsectsandSpiders/Dragonflies-and-Damselflies

Counting Butterflies – Terry Thormin

I had originally planned on posting the second part to “Hunters in the Pond” next, but after having done the first real butterfly count for the Comox Valley four days ago, I thought I should do a quick blog on that. If you have been reading our blogs regularly you will know just how concerned Annie is about butterfly populations on Vancouver Island. Well she is certainly not the only one, and in fact the reason I decided to organize a butterfly count was in the hope that it would provide some data to support our concerns. The problem however is that this should have been started at least ten years ago when butterfly populations were more “normal”.

None-the-less, figuring that any data might be helpful and that we had to start somewhere, I organized a count for July 14th out at Cumberland Marsh, the area where I seem to see the greatest number of butterflies these days. All in all I was quite pleased with the results. The event was run and advertised by the Comox Valley Naturalists Society and a total of 22 people turned out. We split into two parties and spent a total of 3 ½ party hours in the field. The results are as follows:

Western Tiger Swallowtail 16

Pale Swallowtail 3

Anise Swallowtail 1

Cabbage White 5

Margined White 11

Lorquin’s Admiral 11

The total of 6 species and 47 individuals is, I think, quite poor. I am used to doing counts where one dominant species may produce many more individuals than our total and where there are easily twice as many species. Of course biodiversity here on the island is not nearly as great as it is in Edmonton, Alberta where I have taken part in butterfly counts before, but still I had hoped for at least 2 or 3 more species and many more individuals as the habitat was quite diverse with lots of nectaring opportunities. One of the things that might have affected our populations this year is a spring that was cooler, wetter and cloudier than normal and that persisted much longer than normal. Summer weather didn’t really arrive on the island until early July.

Lorquin’s Admiral

There are many factors that can affect butterfly populations, weather, habitat destruction, invasive species, use of herbicides and pesticides and probably a few others that I have missed. As a result it is very hard to determine just why populations are declining. The first thing that has to be determined though is if they are declining, and the best way to do this is through regular butterfly counts. If a count is conducted in a consistent manner in the same area over a number of years it can provide statistics like this.

I suspect that butterfly populations may be declining everywhere in North America, just as bird populations are, but I also suspect that in most areas there is very little data to support this. The North American Butterfly Association organizes annual counts where the data can be submitted online, and this type of count may just work well for your needs. They do counts with a 15 mile diameter, and are conducted on July 4th in the US and July 1st in Canada. They can be contacted at http://www.naba.org . We had tried this type of count here in the past and had very poor participation, so we tried a different approach, picking our own date and making it in a specific locality that was much smaller than the 15 mile circle.

Whichever way you decide to do a count, it can end up being a fun event for individuals and families and, if done consistently from year to year, can provide very useful data. It may also result in people becoming more interested in butterflies, and perhaps open up their eyes to how much butterflies need protection.

Western Tiger Swallowtail

For anyone interested in the Comox Valley Naturalists Society, you can get more information at their website here: http://comoxvalleynaturalist.bc.ca

The European Skipper, Easier to Swallow – Annie Pang

Well, after the thriller that Terry just wrote I am not quite sure how to follow up! We will just have to see what comes to me, what thoughts it has inspired. Clearly he has shown the cycle of life that goes on beneath the water. Clearly he has demonstrated how Nature works… when not interfered with.

And clearly that is not what I am about to do!

The fact is that Nature has been grotesquely interfered with and by solely one species. I will not toy with your intelligence about which species this is. Almost every week I hear some new concern about invasive species and how they will impact man. I hear about how it is necessary to cull native species like wolves, deer, bears, and cougars that have wandered into “residential neighborhoods”. As well, we have sprayed toxic chemicals for Gypsy moth and, by doing so, nearly wiped out the local butterfly populations, and all so we could sell lumber that “might otherwise be infested by the Gypsy Moth”

The truth is that it is we who have invaded and continue to invade the neighborhoods of these creatures. This isn’t news, this is not original thought, but it has to be dealt with and it will be dealt with – and it is already being dealt with by Nature Herself. Our weather is going hog wild and we are actually wondering why? The wrath of Nature is turning on us as we continue to allow our leaders to turn a blind eye to what we have done to this planet and continue to do. In the meantime, oceans are rising as the polar ice melts, eroding coastlines and low lying islands, we are having flash floods, tornado and hurricane “disasters”, extreme weather change; all are killing people. There is drought, famine and disease and these will only increase in severity as we plunder the earth for the sake of our greed and extravagant life styles.

If every human dropped off the face of this planet in an instant, the Earth would survive just fine and within a few hundred years, without us, Nature would completely overgrow and restore Herself and the Earth back to an equilibrium far superior to anything human beings could do or would even be willing to do. Once again the planet would be graced with old-growth forests, meadows of wildflowers and/or glaciers that would completely cover most, if not all traces of our existence. And wildlife would probably sort itself out just fine.

So let us remember that every invasive species got here by the hand of man, and that we are the single most destructively invasive species of all.

With that somewhat less than lovely and charming opening, I would like to introduce an “introduced” (polite way of saying “it doesn’t really belong here and some feel it is invasive”) species of butterfly, Thymelicus lineola, or more commonly known as the European Skipper (also called the Essex Skipper), which has now emerged in certain grasslands in Victoria. To give you a little background on the European Skipper I shall paraphrase what I read from John Acorn’s book “Butterflies of British Columbia”:

This little butterfly was introduced in 1910 in Ontario from Europe accidentally. It appears to have adapted very well to Canada as it spread all across the country right out to the West Coast. Although it is not found everywhere on the island, it is found for a few weeks here in Victoria in several areas. It has not crowded out any of our other indigenous skippers here in Victoria – it emerges several weeks to a month earlier than our native Woodland Skipper and Branded Skipper, and is gone before these two other Skippers do emerge. This beautiful little butterfly exemplifies the fact that not all introduced species are invasive.

Our other local skippers are rarely, if ever, sighted now and any shortage of them appears to have nothing to do with this little butterfly and a lot more to do with habitat destruction. I myself do not pretend to be an expert – I am living in a period when our butterflies are disappearing and so I am very glad to see any butterflies at this point.

Getting back to the European Skipper, I have been observing them and photographing them since 2007 witnessing an enormous number of them emerge at Swan Lake in 2009 with back-to-more-normal emergence numbers in subsequent years. They have in no way affected the large numbers of Woodland Skippers that we see each year that emerge a number of weeks after I have seen the last of the European Skipper.

The first year that I was photographing butterflies, or anything else for that matter, we were walking along the trail circumventing Swan Lake and I saw a number of these tiny little butterflies with their sweet faces through the lens of a camera. Coppery orange in color with black margins on the upper wings, I saw them “skip” from flowering weed to grass to thistle and to clover. I took lots of pictures because there were lots of butterflies and I was in Nature for this first time surrounded by little butterflies. What could be more healing? Well…I can tell you what could be more healing and that was to find them in a variety of colors as well. At the time, I just took for granted that somebody had the answer for this variation of color but have recently discovered this is not necessarily the case

The two colors I most often see are the coppery orange as described in all the books I have read, and another color quite different: it is not orange, but more of a pale, creamy color sometimes even lighter, but with the same black outer margins on the upper wings. It was during my first year I happened to stumble on a real find which was just plain dumb luck. It was a pure white European Skipper with the same black margins. I was told by an amateur “expert” to name it Thymelicus lineola, variation: “pallida” (translation: a pale European Skipper). This person basically tossed it off as nothing to be overly bothered with, but I disagree. I think that when a butterfly changes colors, there is a reason. As our seasons of drought occur earlier and earlier and the grasses dry out, this very adaptable butterfly might very well be adapting.

The lighter variation becomes practically invisible on white clover or dried grass whereas the normal coppery orange color sticks out and attracts the attention of predatory birds like the fast, swooping swallow, who is feeding its young this time of year. This I can honestly say I have seen, and when at Glendale Gardens last week, I was blessed with the opportunity of seeing and photographing two baby swallows in a bird box being fed by their parent(s). Swallows are great at catching insects in flight and are so fast that unless they are perched, they are nearly impossible to photograph, especially with my little camera. So I am very thankful I saw these sweet little darlings (how very unscientific of me) so close. They were Violet-green Swallows, as it turns out, and the parents are lovely to behold….when they are still enough to behold, that is!

But I digress. It was only a few days later, after seeing the swallows at Glendale Gardens (Horticultural Centre of the Pacific) that I went to a section of the Swan Lake trail looking for any sign of the Milbert’s Tortoiseshell, yet another butterfly I hope to photograph this summer, when John spotted a tiny butterfly or “moth”. Without even looking I knew it must be the European Skipper and it was. The timing was about right. I found what I consider to be the common copper color and the light or “pallida” variation. I may be imagining this but what I want to point out is that each year there seems to be a higher number of the lighter variation although still not as easily found as the coppery orange shade. As well, I have seen the copper ones chasing off the paler ones. Discrimination? Could be. One Lepidopterist told me that not a lot of research had been done on “T. lineola” (yes, you guessed it; the short form of the scientific name).

It gives me great comfort to know how adaptable butterflies can be. The Western Tiger Swallowtail, although not out in the numbers I used to see, has survived our cool, damp spring and early summer in sufficient numbers to procreate. At Knockan Hill, we saw no fewer than six of them and that was only in the sections of Knockan Hill Park where we went. Another day a friend of mine reported seeing 10 Western Tigers at Government House in another area of Victoria.

And after first sighting them, I found the European Skipper on Christmas Hill, otherwise devoid of all butterfly life with the exception of a solitary Western Tiger Swallowtail; and also at Islandview Beach where the only other species we found was the Lorquin’s Admiral, and in good numbers. I know they have been seen in other areas as well and where I do see them, I usually find Swallows as well, but don’t expect to find the European Skipper in your garden unless you live right near a bog or grasslands, for they are not nearly as widespread as the Woodland Skipper that seems to pop up everywhere in August.

Having perhaps given you a bit of a jolt with my opening, I hope you enjoyed this little story about a little European butterfly that came here long after we invaded North America and who has really done us no harm from what I have heard, read and seen. I am glad it is here and for the next few weeks it will tide me and the swallows over while I wait for the few other butterflies we get these days to come out. I am grateful to this little butterfly for being so photogenic. It provides food for the swallows and food for the soul of this particular homo sapient “specimen”.

Having said this, I heard some alarming but not surprising statistics on the news as well: the insect-eating bird population across Canadais down by 15%, but in Southern B.C. alone, it is down by a whopping 35%!! The Barn Swallow was featured as one species that was showing a decline in numbers but I am sure there are many more. It seems that this would be consistent with the declining insect population, for at Islandview Beach there was not a single mosquito, and it is usually filled with them by now. Only a few darners, one of which I’ve enclosed a shot of (a Blue-eyed Darner), were evident and they too prey on insects, even on other dragonflies. It would seem the entire food chain has been disrupted and we are seeing the results.

If we are to continue and survive we might learn something about adapting to our environment so that we are less apparent, rather than more so. We should follow the example of my little “pallida” and try to blend into the environment rather than exploiting it.

In one of my next blogs I, hopefully, will get around to the subject I have wanted to write about for a while now; how as Canadians, and particularly islanders, we can provide food for ourselves and learn how we can transform our wasteful land resources into places of biodiversity, as Terry blogged about before, and as sources of food both for ourselves and the environment.

In the meantime, I shall leave you with another poem.

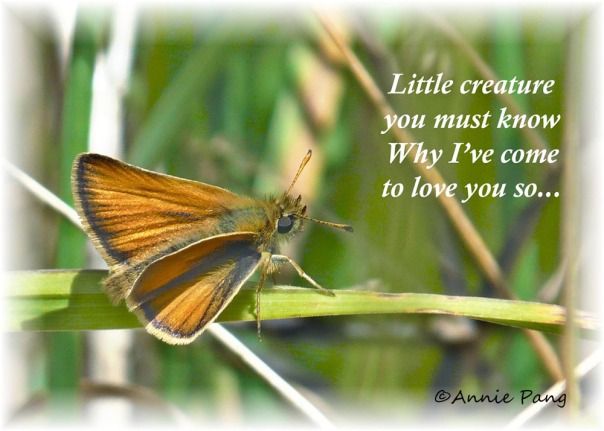

Song to the European Skipper

Little creature you must know

why I’ve come to love you so.

From your home you traveled far

by hand of man—now here you are.

Darting here and darting there;

closer look, a face so fair,

tiny wings and body hair.

How can I begrudge you space?

You, I welcome to this place

with your tiny elvish face.

Beauty has each butterfly,

beauty that can teach the eye

that this place we have to save

for the butterfly so brave.

Nature holds us in Her hand

and She makes her own demand

not caring if we understand.

We may cause our own demise

if we callously despise

all the balance that once was

because we could, or just…because.

Little creature you must know

why I’ve come to love you so,

though some claim that you invade

causing other ones to fade.

Man continues to encroach

worse than any wanton roach,

and what’s worse, it’s not from need!

No! It’s fuelled by our greed

for the dollar, for the buck,

for a better car or truck.

What do we care what we harm,

then we cry out in alarm

from the flooding or the quakes

never owning our mistakes!

Listen to the screams She makes;

Nature comes, now it’s her turn!

Will we listen? Will we learn?

Or keep drilling for black gold,

and let the leaders have us sold.

Blame a little butterfly?

“It’s invasive” so they cry.

No! I greet you with a smile,

hoping you will stay awhile;

take a picture while you pose

in the sunshine where you doze,

or darting here and darting there,

little butterfly so fair…

© Annie Pang July 7, 2012.

Hunters in the Pond, Part 1 – Terry Thormin

The young cutthroat trout swam warily through the water. At 8 cm ( just over 3“) long it was still quite small, even by fresh water standards. Cutthroats that stay in smaller fresh water ponds all their lives rarely get over 40 cm (16”) long and two pounds in weight, whereas saltwater populations can weigh up to twenty pounds. The cutthroat was looking for food, any insects would do. But right now it was not having much success. To avoid being taken by a kingfisher or a great blue heron it had kept to the centre of the pond and was hunting in deeper water, but lack of success had driven it in closer to shore. It was now searching amongst the emergent rushes along the shoreline.

It never even saw what hit it. Suddenly from the leaf litter at the bottom of the pond powerful front legs shot out and grabbed it around the middle and heavy spines punctured through its scales, holding it fast. It jerked violently as needle-like mouthparts pierced through its scales to its very core. The pain of the toxic digestive juices was overwhelming but all its struggles were for naught. As digestive enzymes turned organs and muscles to soup, its struggles became weaker and weaker until finally the life slipped from its body.

Giant Water Bug with Cutthroat Trout

The Giant Water Bug feasted for a full day before it was satiated. It was at its penultimate stage and it now had the body reserves it needed to go through the final molt to adulthood. It released the cutthroat which floated to the surface and became food for scavengers. It searched out a place close to shore in amongst the floating vegetation where it could stick its breathing tube out of the water while its old skin split down the middle of the back and the new adult, complete with wings, emerged. Even as the ponds top insect predator, this was a dangerous time for the giant water bug. Its new exoskeleton was soft and offered no protection, and even much smaller insects could attack and kill it at this stage. It would be several hours before its exoskeleton was hard enough to give it proper protection.

Giant Water Bugs are just one of many types of insect predators that are found in fresh water bodies. They are ambush predators, sitting amongst dead leaves and other debris at the bottom of ponds waiting for something to come close enough to grab. They are superbly camouflaged for this purpose. As well as taking other insects and small fish, they have been known to kill frogs, turtles and even snakes. Their bite is considered to be one of the most painful of all insects, and has earned them the name toe-bitter. The largest North American species is Lethocerus americanus, and the biggest of individuals can get up to 65 mm (more than 2 ½”) long. Females of this species, and others in the genus, lay their eggs in a mass on emergent vegetation. Females of other genera lay their eggs on the backs of the males. This affords the eggs better protection from predators while both aerating them and keeping them moist. In the tropics some giant water bugs can get up to 12 cm or more than 4 ½ “ long. There are about 150 species worldwide.

Adult Giant Water Bug

Predaceous diving beetles are another family of ferocious predators found in fresh water bodies. These beetles range in size from about 1 mm to over 44 mm (0.05 to 1.75”) in length. Unlike Giant Water Bugs they are active hunters, often searching the bottoms of ponds for their prey which mostly consists of other insects, tadpoles and small fish for the largest of species. Adult beetles are air breathers and have to regularly come to the surface to get more air. When they dive under the water they carry a reserve layer of air under their wings alowing them to stay submerged longer.

Predaceous Diving Beetle

The larval stage looks quite different from the adults and these are called water tigers. Like the adults the larvae are fearsome predators with needle like jaws. There are about 4,000 species worldwide.

Water Tiger

A third group of aquatic predatory insects is the back-swimmers. This is another family of true bugs, and all species are active hunters. Unlike other aquatic insects they spend their lives swimming upside-down, hence the common name. Like the giant water bugs and predaceous diving beetles they swim with their back legs which are modified for that purpose. In the backswimmers those legs are exceptionally long and look very much like oars. These bugs are primarily insect eaters although the largest of species, which can get up to 2 cm (0.8”), will take small tadpoles and fish. They regularly come to the surface of the water for air, which they carry with them as a silvery sheen on the under surface of the abdomen. They are often seen hanging upside down at a 45 degree angle from the under surface of the water, ready to swim quickly downward if danger threatens or they see potential prey. There are about 400 species worldwide.

Backswimmer

All three of the above families of insects have one thing in common, as adults they have wings and can leave the water and fly. They use this primarily as a dispersal mechanism. Most flights happen at night when the insects use the moon for navigational purposes. If you use the moon for navigational purposes, as long as you keep the moon in the same relative position in the sky and you do not travel for a long period of time, you will travel in essentially a straight line. Unfortunately when insects try do this in the presence of bright lights they end up flying in an ever diminishing spiral around the light until they come in contact with an immoveable object like a wall or the light itself. I am sure that everyone has seen the results on the wall behind their porch light or below a particularly bright street light are at the very bright lights at many gas stations. Inevitably this ends in the premature death of many insects. It has also earned the giant water bug another colloquial name, the electric light bug.

There are three other groups of aquatic “bugs” I would like to write about, actually two insects and a spider, but before this blog gets way to long, I will quit here and save the others for a second blog.

Death Stalks the Pond

Beneath the pond, amidst debris,

the water bug waits patiently.

She hides amongst the leaves so well

her presence is so hard to tell

The fish swims by unknowingly,

until it’s hit most forcefully.

Spined legs dig deep and hold it tight,

and needled mouthparts start to bite

Death stalks the pond

As on its flesh the bug does feed,

the fish provides what the bug needs,

to grow and molt and finally be,

an adult, its true destiny.

She finds a male, mates and with tact

lays rows of eggs upon his back.

And every egg has life within,

another cycle to begin.

And life goes on

©Terry Thormin July 4, 2012

The Magic of the Butterfly – Annie Pang

Sometimes when I am out in the field looking for one thing, I find something else quite unexpected, and in this case it was a very welcome thing to find indeed. It was a warm, sunny Friday on June 29th and I had convinced John to take the afternoon off and help me track down a few sightings that had not been photographed by anyone that we had heard of. Our first stop was Mt. Tolmie where Painted Ladies and even a West Coast Lady had been sighted two days before. But it had rained Thursday and been very unpleasant so there was no point in looking. Friday was a surprise as it was supposed to rain again but the sky cleared and the day became sunny and warm. I found it uncomfortably warm because here in Victoria we’ve become so used to the cool climate we’ve had so far this year that anything above 17° Celsius feels downright hot.

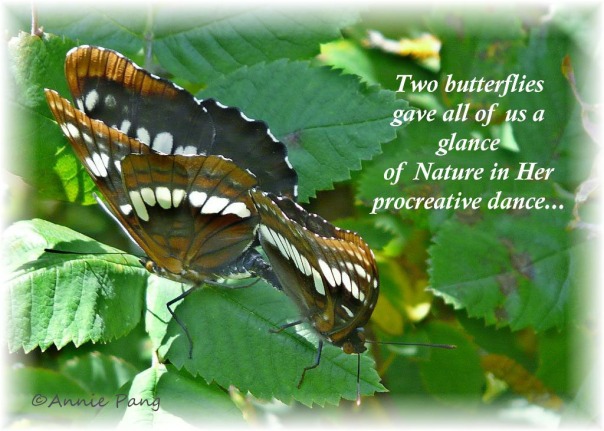

We drove up to the top of Mt. Tolmie slowly but saw no “Ladies” of any kind. Discouraged, I still grabbed my camera out of habit as I left the van. I walked towards the path where I had heard a Red Admiral had been sighted as well, then turned to avoid it because I saw some young people playing rather loud music all crowded into the brambled walkway I really wanted to check out. But something caught my eye and caused me to stop. I took a closer look and saw that they had really good cameras; expensive DSLR’s for sure. I had a funny feeling that I should see what they were up to. It was a good move in so many ways. They were photographing two Lorquin’s Admirals, a male and female, locked together, mating on Himalayan blackberry leaves. I commented to them on the species as I looked on and started taking shots of my own. We all sort of melted together at that point, enthralled by what we were seeing. Their exclamations, and, frankly, my own, brought us together as lovers of these beautiful creatures. I could see these kids had good hearts and apparently so could the butterflies!

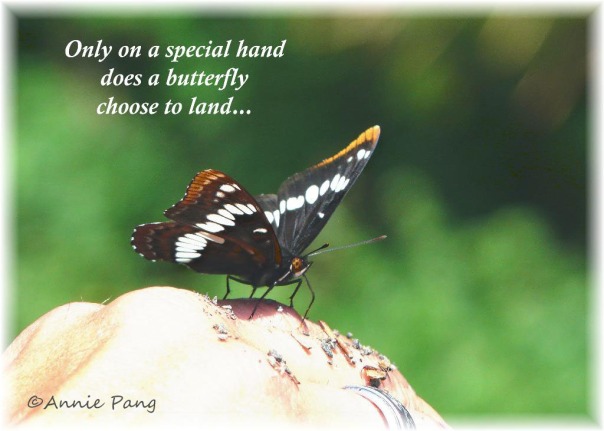

Done mating, the butterfly pair separated and one took off almost instantly. The other stayed behind and flew around us. “T.J.”, for that was one young man’s name, crouched down and started talking to the butterfly. His music was still blaring away from his backpack, but I think he and the butterfly were both oblivious to it. He put his hand out onto the ground where the Lorquin’s had landed a number of times. It landed again and then, wonder of wonders, it crawled right onto his fingers. We all just stared. But not for long!

“Quick, man, take some pictures” whispered T.J. to his friend, Peter. We all took pictures, we were all talking, joined together in this experience by the grace of a butterfly. I explained that butterflies were sensitive to sudden motion as opposed to noise, so T.J. was very slow and gentle. I encouraged them to take side shots as well because the Lorquin’s Admiral looks different with wings shut. Funnily enough, as if on cue, the Lorquin’s Admiral on T.J.’s hand slowly closed its wings and there were more sounds of wonderment that gladdened my heart as we all took pictures with the grime of the ground still on his hand where the butterfly “posed”. Nobody cared about that, so caught up in the moment as we were.

T.J., Peter and Mackenzie, their pretty lady friend, turned out to be our future for tomorrow. Our hope for tomorrow. I watched them, marveling in awe at the butterfly sitting sedately on T.J.’s hand. It stayed there for an uncanny amount of time – even I was surprised and I’ve had plenty of butterflies land on me. It really felt like this butterfly was trying to tell us something, something very important. This time it chose to reach out to some young people and that made my mission so much easier; to educate and raise awareness of our diminishing butterfly population.

Out of a bit of excitement, T.J. turned suddenly to talk to us and the Lorquin’s took off. But as it departed, T.J. simply said to it “Thank You, thank you…” and turning back to us he exclaimed “Man, I’m just sweating!” And I knew he understood what it was like to experience that magical moment when a butterfly lands on your hand, on your foot or on your head – there’s nothing quite like it. And it is an experience that T.J. is not likely to forget either. He told me he would have no problem remembering it was a “Lorquin’s Admiral” after that experience. And then he put out his hand and introduced himself to us both, as did Peter and Mackenzie. I mentioned our blog site to them in case they were interested in finding out more about our local butterflies and was quite surprised at their enthusiasm and, needless to say, extremely pleased. These days it is such a pleasure to find young people who are genuinely interested in things outside of themselves. And especially when that interest turns towards Nature. It was a gift to me to meet them and I asked them if it was okay if I wrote a blog about my experience with them. Not only did they readily agree but they even gave me permission to use their names, and so I have.

The Lorquin’s Admiral brought us together; two different generations with nothing in common – nothing except everything that really mattered. I heard in their eyes, their worries about the future of this planet they hold dear, that is their home. I saw in their voices, behind the cigarettes, loud music and cheerful but sad smiles, the words “I’m scared and I’m glad we met so we could share this bit of magic that is left.”

I felt the imploring call, “Please keep doing what you are doing…”.

We went on our way after that and I felt very good about the entire experience. It appeared that I had made some progress, that the world had made some progress in that instant of time with those young folks. We got in the van and drove on towards Mt. Douglas, commonly known as Mt. Doug, our next destination. Driving to the top, I was still hopeful that I would find the “Ladies” or a Red Admiral. Getting out of the car and clamoring around the rocks at the peak I found nothing. Perhaps it was time to go home. Then out of the corner of my eye I saw something large and bright and I turned. I didn’t care that these were not the butterflies I was looking for. At this point, finding ANY butterflies would be a blessing to me for I had never seen so few nor witnessed such a cool spring, aside from a handful of days where temperatures reached seasonal levels.

Out of desperation I scrambled through bushes and weeds, nearly twisting my ankle, which was careless of me, but such is the way of things when finding something I so desperately wanted to see; another butterfly or even two. Yes! There they were, gliding around a grove of Oceanspray shrubs. Two beautiful Pale Swallowtails. There was no mistaking the wide black margins or the creamy-white “stripes”. And this was the right habitat for them as well. I have seen more Pale Swallowtails this year than in any previous year and have no idea why that is. Though nearly always at higher elevations, I have also found them near sea level as well. I have read that the males “cruise” around at higher elevations looking for prospective mates. There has been some speculation on the part of one long-time enthusiast about whether they hybridize with Western Tigers, but according to John Acorn’s “Butterflies of British Columbia” they do not, and I certainly have not seen what I would call a hybrid, ever. A faded Western Tiger can “appear” to look like a Pale Swallowtail, but the Western Tiger has thinner black margins and black stripes and their lighter areas are more evident than on the Pale. In flight, there really is no mistaking a Pale with a Western Tiger. And in this case, I was happy to see two…probably both males as they were fighting over territory.

I began to sing my little butterfly song, a song with no words. Really, I think it is to calm ME down so I become invisible to the butterfly rather than a vibrational “lure” to the butterfly. It doesn’t matter because it usually works, and today was no exception.

The circling Pale landed several times on a leaf or on Oceanspray….plenty of time for me to get the shots I so wanted.

And then something came flying in to chase it off!! It was a Red Admiral! It was only there long enough for me to get a good look at the circle of red on it’s upper wings, and then after a brief instant, it vanished!! Although the Pale returned and landed and I waited and waited, the Red Admiral didn’t return and neither John nor I could find it anywhere.

I didn’t mind. There is still a lot of summer to go as it has barely begun. And it was my turn to say, “Man, I’m just sweating!”. John helped me get back out of the little miniature grove I had scrambled down to and, very tired in a good way, we headed off.

Glad as I was of my Red Admiral sighting and shots of the Pale Swallowtails, my mind kept going back to the experience on Mt. Tolmie with those three fresh young faces, lit up with wonder at the literal “first hand” experience of that Lorquin’s Admiral. Maybe the future isn’t so bleak, if we can get young people involved in our environment and pass along what we know, and more importantly, listen to their voices of protest about what we will be leaving them to inherit.

Perhaps the silent voices of our butterflies isn’t as silent as I thought. Time will tell…yes,time will tell…

It holds the magic of the butterfly…

Amongst the brambles and the Ocean Spray,

I found myself within a special place.

I found eyes searching in a youthful way—

I found some hope within each fresh new face.

Together, joined by Nature’s blissful grace,

two butterflies gave all of us a chance

to share Her secret reproductive race—

two butterflies in procreative dance.

Three youths, with hopeful eyes, spoke to my heart

and to a butterfly, held out a hand.

It heard their silent screaming, helpless cry,

and came upon those fingers in the sand.

And in that hand soon all our fates will lie—

it holds the magic of the butterfly…

Dedicated to T.J., Peter and Mackenzie with thanks for letting us share your experience and recount it to our readers. May you keep hope alive within your generous hearts as well as your love and respect for Nature and willingness to learn more about preserving It.

© Annie Pang June 29, 2012.