Blog Archives

9 km Bog Revisited – Terry Thormin

I took another trip up to 9 km. Bog two days ago. I was particularly interested in photographing two things, the Swamp Gentian, Gentiana douglasiana, a plant that is quite common in the bog, but that I have never taken the time to photograph, and the Ringed Emerald, Somatochlora albicincta, a dragonfly which is also common, and I have tried to photograph many times, but have never succeeded. The Swamp Gentian was the easy one, although it was certainly not a case of simply finding a plant and photographing it. These gentians grow low in among the sedges and as a result are difficult to photograph with a nice clean background. After spending quite a bit of time looking for a suitable plant I finally realized that there was only one way I was going to get the photo I wanted. I plucked a single plant out of the ground and wedged it in a crack in one of the many bare tree stumps in the bog and got my photo that way.

I try avoiding doing this sort of thing, but when a plant is so common that you trample them with almost every single step you take, somehow sacrificing a single plant for the sake of a photo doesn’t seem that bad, especially considering that I am one of only a handful of people who ever even visit this bog.

While I was at it I also photographed two other plants using the same technique. Bog cranberry, Oxycoccus oxycoccos, is another tough one to photograph as it is a low creeper with tiny leaves and flowers. The tiny flowers of this plant remind me of miniature shooting stars, Dodecatheon sp.

My final plant was the Great Sundew, Drosera anglica, which I have photographed before, but when I found a particularly robust plant with lots of leaves and some flowers as well, I couldn’t resist. Again I used the same technique, but in this case I just lifted the chunk of moss it was growing in from the ground and placed the whole thing on a log. Because nothing was rooted to the ground I was able to replace plant and moss right back where they came from.

I held little hope of getting the emerald’s photo as I had tried many times before without success, but well, you have to keep trying. The problem is that the few perched individuals I have seen have been very wary and have flown before I could get close enough to get a photo, and the flying individuals, which are quite common, only seem to hover very briefly. On this occasion I was siting on my portable 3-legged stool taking photos of another plant when an emerald stopped and hovered almost right in front of me. I quickly got my camera up and took a burst of about 5 photos, then the dragonfly moved slightly and hovered again. Another burst of photos and again the dragonfly moved slightly and stopped to hover. Twice more it repeated before it finally decided to fly off, leaving me amazed and ecstatic. Although many of the images were out of focus because the dragonfly was moving slightly, I managed to get seven shots that were quite good. So here are two photos I’m quite happy with.

Dragonfly Time – Terry Thormin

The earliest dragonflies up here on Vancouver Island start flying around mid-April. But it is not until late June or early July, depending on the year, that things start to get really active. Well things are active now and I though I would write a short blog about it. My favorite place to photograph dragonflies is Little River Pond, a man-made pond a short 8 minute drive from my home. I have recorded 20 species of dragonflies there and on a typical summer day will regularly see 10 or more of those species. I spent a pleasant 2 hours there yesterday (June 25) and although I only saw 9 species, it was the number of individuals and level of activity that was impressive. Here are a few of the photos I took.

I will often provide a perch for dragonflies at Little River Pond. This is particularly helpful for the Common Whitetail which normally perches on bare ground. On this occasion a Four-spotted Skimmer decided to use the perch, and I couldn’t resist taking its photo. At a distance this is one of our drabbest dragonflies, but up close a freshly emerged individual is a real gem.

The Blue Dasher will often land on a perch I provide, but I much prefer it on a natural perch. The problem is that often it perches fairly deep in the grass where getting a shot without a cluttered background is difficult. On this occasion it landed on a grass stem that was isolated enough from the rest of the vegetation that I was able to get the out-of-focus background I wanted.

That Common Whitetail that I was hoping would land on my perch actually did many times and I got several shots of it. In the end though my favorite shot was one on a grass stalk. This was a coulorful grass stalk, aging and turning orange, and I had seen a Four-spotted Skimmer land on it and thought that would make a good photo. I set myself up and waited, and before the skimmer landed, a whitetail decided to land briefly and I got this shot. I decided to leave the dragonfly fairly small in the photo to enhance the composition with more of the grass stalk.

I couldn’t resist adding one last photo. I love the challenge of shooting dragonflies in flight and on this occasion the shot I got was of a pair of Cardinal Meadowhawks flying in tandem and ovipositing in the pond. For those of you who love dragonflies as much as I do, happy dragonfly hunting, and for those of you who haven’t developed the passion yet, I hope a little bit of this rubs off.

The Pond – January – Terry Thormin

Winter rains have filled the ponds, causing them to overflow their banks, flood the gravel bar at the southeast end and the low area between the two ponds, and create a single, large pond. It now looks much like it did when I first saw it, causing me to name it in the singular – Little River Pond. It will remain like this until the rains stop and the heat of summer evaporates much of the water. Most of the gravel bar is under water and much of what isn’t, is just barely above the water level. I have to wonder how the tiger beetle and sand wasp larvae can survive in these conditions, but every spring the adults appear again. For now, though, the gravel bar is devoid of life.

Little River Pond showing flooded narrows

Not all life is silent, though. The bald eagles regularly fly overhead, giving their weak, high-pitched chirping whistles in antithesis to their massive strength. An occasional crow or raven gives out its rasping call and the local flock of red crossbills flies from tree to tree looking for seeds to eat and calling “jip, jip” as they go. chestnut-backed chickadees and song sparrows forage in the bushes around the pond, and from the small patch of woodland across the pond a spotted towhee gives a raspy “zreeee.”

Red Crossbill (photographed in 2007 in Edmonton)

On the pond you may hear an occasional “quack quack” from a mallard as the small resident flock forages among the flooded bushes between the two ponds. There are other ducks as well. The ring-necked ducks are usually present, but wary, frequenting the far shore and swimming into the bushes if they feel threatened. The two female buffleheads that are usually present don’t seem to be as wary, and if you are quiet they may swim close by you, diving regularly for whatever they can find on the bottom of the pond.

Bufflehead

Earlier in the winter I had noticed a large number of freshly cut branches at the entrance to the beaver lodge. It was obvious that the beaver was stocking up on food for the winter. Beavers will remain active all winter long but will stockpile branches in the fall to minimize how frequently they have to go out foraging for food in the winter. During the summer months they feed on fresh green shoots and roots of plants, but in the winter they have to feed on tree bark, and for this purpose they will sometimes cut down quite large trees.

Beaver lodge

On one of my visits to the pond I had the opportunity to talk with a local resident, who told me that the beaver had finally felled a large tree at the west end of the pond earlier in the winter. I walked down to the west end and found the tree the beaver had cut down, a large cottonwood with a diameter where the beaver had cut it of about 60 cm (2 feet). Most of the side branches had been cut off and much of the bark on the main trunk was chewed away. Obviously this was the beaver’s source of food for the winter.

Cottonwood stump

Cottonwood trunk stripped of bark

January has been rather average weather-wise, although I suspect that we have had less sun than average. Daytime highs have generally been up around five degrees and the warmest day hit nine. Although we have had a fair bit of rain as usual, and the occasional wind storm that typically comes down the Strait of Georgia, there has not been a major winter storm with a dump of snow this month. At Little River Pond no ice formed other than overnight ice in the shallow, flooded areas, which quickly melted as daytime temperatures rose.

Life in the water slows down in winter, but activity never completely stops. The only evidence of any fish I saw was a single fish jumping on January 1, most probably a sea-run cutthroat trout. This doesn’t mean that the fish aren’t there; they are simply not rising to the surface for insects. The adult cutthroats, which are typically found in sheltered estuaries and tidal lagoons, return to fresh water in late fall and early winter and spawn in late winter to early spring. The young stay in fresh water for two or three years before they migrate to the ocean.

I did a couple of sweeps with my insect net to see what I could find in the water. My net has a very fine weave so it collects even the tiniest arthropods.

The first sweep was shallow, through the vegetation, so that I avoided getting any of the bottom muck. I transferred it to a large plastic jar that I keep just for that purpose and immediately, even through the murky water, I saw life. A tiny predaceous diving beetle, probably less than 3 mm long, rose to the surface for a bubble of air. Then I noticed several damselfly nymphs swimming in the murky water. I decided to bring the jar home to let the silt settle out of the water.

Damselfly nymph

By the time I got home it was obvious that the water was teaming with life. There were at least a dozen damselfly nymph, a number of caddisfly larvae, a couple of daphnia, several cyclops and numerous tiny arthropods that I finally decided must be clam shrimp. The last three were all around a millimeter or less in length, just barely visible to the naked eye.

Caddisfly larva

I did my second sweep almost three weeks later, and this time I went deep into the muck, looking for larger aquatic insects. Sure enough, I dredged up two dragonfly nymphs, which was not in the least surprising as this pond has such a high number and diversity of dragonflies.

Dragonfly nymph

I also got a water boatman and a small predaceous diving beetle larva, also known as a water tiger, and this time there were lots of caddisfly of at least three types. It is these larger creatures that are necessary to sustain the fish population.

Water tiger with cyclops at lower left

With temperatures often ranging into the high single digits, I really expected to see at least a few insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. I was not disappointed – on almost every visit I saw at least one or two small flies, most likely midges of some sort. On one occasion I took the time to overturn a few logs, and on my third attempt I found several very active European sowbugs.

European sowbugs

That same day I found a larger fly lapping up some juices from bark remaining on the cottonwood tree trunk that the beaver had felled. This is probably an anthomyiid, or root maggot fly, although according to Matthias Buck at the Royal Alberta Museum, there is a possibility it is a muscid. Flies in these two families are often so similar that it is impossible to identify them to family, let alone genus or species without collecting them.

Fly, either anthomyiid or muscid

Now, as the end of the month draws near, the days are getting noticeably longer and soon the first signs of spring will start to appear. But I’m not holding my breath; I know how cruel winter can be, and a serious winter storm is always a possibility in February. My one consolation is that here on the coast such storms are often followed by rain that quickly melts the snow away.

JANUARY

As winter’s winds roar down the strait

the pond lies silently,

broken only by eagle’s screams,

a small cacophony.

But all’s not dead, for in the pond

life stirs ’gainst winter’s hold.

A caddisfly, a diving beetle,

a dragonfly nymph bold.

And on dry land a thorough search

‘neath logs and dead leaf litter

reveals more life that’s active still,

sowbugs and other critters.

But most are dormant, most await

in silent slumber too,

for the first sign of spring’s return,

to begin life anew.

©Terry Thormin

Note: I am posting this blog on World Wetlands Day, a day that is meant to draw people’s attention to the need to protect wetlands everywhere in the world. If you have read this this blog and not read the introduction, which was the previous post, I reccommend that you read it as it will set the scene for this ongoing blog and will also reflect the need to protect wetlands. You can find more information on World Wetlands Day here and you can find the introduction to The Pond blog here.

Merlin and the Dragons – Terry Thormin

I went to Little River Pond again today. It was another warm fall day with no wind and I was hoping to see some late Sand Wasps, but there were none present. It has been over three weeks now since I last saw them so I am assuming that they really are finished for this year. There were still a number of dragonflies flying and I saw three species, at least a couple of Blue-eyed Darners, probably 6 to 8 Canada Darners and at least as many if not more Saffron-winged Meadowhawks. It took me a while to get a positive identification of the Meadowhawks as they were landing on the bare sand rather than up on the grasses the way I had seen them before. This is typical behavior for the Striped Meadowhawk, but a close look told me that they were Saffron-wings. For the next hour I tried to get one to perch up on a grass stem or seed head, but with no luck. I did get some shots of them on the sand and have included one here.

After an hour of frustration I finally decided to give up and head back to the car. Just as I was leaving a Merlin flew in to the dead branches at the top of a large birch tree near the edge of the pond. It had a dragonfly, a large darner, that it had obviously just caught and it proceeded to tear the dragonfly apart and devour it. Out came my camera and I got off several shots before it finished.

It then sat there looking around intently at the pond until it suddenly launched itself off the branch and flew out again. This time it returned empty handed, or should I say empty clawed.

Six times it made a pass at the pond sometimes launching out in a slight decline, other times going immediately into a power dive. I am sure that this was a function of how far away the dragonfly it had spotted was. Three of those six times it came back with a dragonfly which it promptly ate.

It was still hunting the pond when I finally left. I expect that if I go back to Little River Pond again in the next few days there will be far fewer darners. This particular Merlin was a Pacific race bird, the subspecies that nests on Vancouver Island. It is very dark with a heavily streaked breast, the streaking being so heavy in the middle of the breast that they run together becoming an almost solid dark breast.

I have talked about the Merlin’s propensity for hunting dragonflies, especially the large Common Green Darner, in previous posts, but this was the first time I was able to photograph it in action. Of course the really great shot would be of the bird in the process of catching a dragonfly or even in full flight with a dragonfly in its talons. But perhaps that is another blog.

The Autumn Meadowhawk – Terry Thormin

Back on August 29th I wrote a blog called Vancouver Island Dragonflies, 2012 Season. In that post one of the things I said was that the Autumn Meadowhawk had not put in an appearance at that time. This seemed rather worrisome to me as last year I saw my first individual on August 16th. Well they have now turned up, and in good numbers. I saw my first on September 6th, just a single individual, and then a few on the 12th, but today they were numerous.

Everywhere I looked along the shore of Little River Pond I saw pairs flying in tandem and laying eggs along the edge of the pond. In one stretch of preferred shoreline that was only about 2 feet long I saw 6 pairs of Autumn Meadowhawk ovipositing, and the total number of pairs along the edge of the pond had to be well over 20, and for a small pond like this that was quite impressive.

The pairs would fly in tandem just over the shoreline, hovering briefly and then dipping down to allow the female to reach down and touch the tip of her abdomen either in the water very close to shore, or in the matted vegetation just above the water line, each time laying a single egg. With the water rapidly receding at this time of year all the eggs will shortly be out of water. The eggs will not hatch until the fall rains fill the pond again, causing the eggs to once again be submerged.

Autumn Meadowhawks flying in tandem

As well as the pairs busy ovipositing, I also saw a number of individuals flying around and perched on the vegetation. Most of these appeared to be females, although I did see at least one individual male. This species is not only the last dragonfly to emerge as an adult in the summer, but is also the last one flying in the fall, with some individuals lasting into mid November if the weather stays warm enough.

Autumn Meadowhawk female

Autumn Meadowhawk male

As well as the Autumn Meadowhawk I had four other species today, the Striped Meadowhawk, and three darners, the Common Green, Blue-eyed and Canada. It is encouraging to see this many dragonflies in September this far north and it was particularly encouraging to find out that the Autumn Meadowhawk was not absent this year, just late, and present in good numbers. I will continue to go back to Little River Pond to see how long each of these species hangs in and who knows, with a little bit of luck my last dragonfly blog may be in November.

Photographing Dragonflies Revisited – Terry Thormin

I wrote a short blog about photographing dragonflies in flight a while back, but after my recent post on Vancouver Island Dragonflies I had so many responses commenting on the photography and questions about how I get the photos that I decided I should expand my original post.

First a brief note about what equipment I use. Up until a little over a year ago I was using a Canon super zoom point and shoot, the power shot SX1 IS, and even with that camera I occasionally got decent in-flight shots of dragonflies. Here is one of those photos.

My camera now is the Panasonic micro four/thirds DMC G3. Most of my photos are taken with the 100 to 300 mm lens, but for close head shots of perched dragonflies I will attach the Canon D500 close-up lens using stepping rings to the front of the zoom lens.

For in-flight shots this is a nice light camera, easy to hand-hold, and it produces quite good results. Any DSLR with a good quality lens in the 400 mm range should do quite well though.

For perched shots I prefer to use a tripod whenever possible. This often allows me to shoot at a slower shutter speed thus increasing my depth of field and getting more of the dragonfly in focus. The real trick to getting good perched shots is to isolate your subject from the background. Getting as much of the dragonfly in focus as possible while still having a nice out-of-focus background is often a real challenge. I regularly pass up opportunities to shoot subjects just because I know that there is no way I will get the separation of the background I want. Often just getting down to the level of the dragonfly will help solve this problem. Insect photos with messy backgrounds just don’t look good in my opinion, and dragonflies, with their large, clear wings are particularly bad. I think the following shot illustrates this point quite well.

Compare the above shot to the following one and I think you will see what I mean.

I am constantly keeping in mind where the sun is as in most situations I want the sun behind me when I shoot dragonflies. This eliminates harsh shadows and over exposed highlights. I also look for nice perches; a dragonfly perched on a nice seed head is far more attractive than one perched on a bare stem.

Many dragonfly species will defend a specific territory and will use the same perch over and over again to do so. Sometimes it is possible to substitute a more attractive perch if the original is not great.

So sun behind me, nice perch, a balance between good depth of field and good separation of the dragonfly from the background, and if all else fails use photoshop to fix the problems as best I can.

Shooting dragonflies in flight is quite different, and far more challenging. I would have to say that the most important thing you need for this type of photography is patience. There are a number of tricks and hints that I can give you to increase your odds. First your best chance of getting these shots is to get the dragonfly when it is hovering. Getting shots of dragonflies in full flight is next to impossible. I say next to impossible because I have seen shots where the photographer said the dragonfly was not hovering, and I choose to believe the statement. The reality is that you will have enough of a challenge when they are hovering and that is much easier than when they are not hovering. I will talk more about hovering in a bit.

I never use a tripod when taking in-flight shots. Most dragonflies hover so briefly that it is hard enough to get on them without a tripod, and a tripod will slow that process down considerably. Next, I pick my places. This generally requires some scouting around. You need a place where the dragonflies hover regularly, where the sun is at your back, where there are good site lines and where there is a decent background. I avoid cattail marshes unless there is a gap in the cattails or I can get above the cattails. Generally I end up at marshes or ponds with low, sparse shoreline vegetation or in the middle of a bog with low vegetation. One of my favorite places, Little River Pond, has a spot where there is a good gap in the vegetation and I can set up my camp chair and spend hours waiting for the right opportunities to come along. Many dragonflies will regularly patrol the edge of a small pond and waiting patiently often pays off.

When shooting perched dragonflies I shoot on aperture priority at 200 ISO, but shooting in-flights is quite different and I use two different settings. The first is shutter priority at 1/1000 of a second and ISO 400. I would go to a higher ISO except that my camera becomes too noisy above 400. If you have a camera like the Nikon D700 then push your ISO as high as you feel comfortable and shoot at a faster shutter speed. It is a good idea though to leave some room for an increased depth of field, and I find that 1/1300 of a second does a pretty good job. I know everyone is different but I am not a big fan of perfectly sharp wings right to the tip, at least not with dragonflies. I think that the blurred tips give a better sense of motion. I also use single area focusing as I find that when using multiple areas the camera is more likely to focus on something in the background. This setting is ideal for places where the background is a uniform colour and shade. I use it when I am in a bog or an open field with uniform green vegetation. It then allows the camera to automatically adjust the exposure should you get some cloud cover.

A quick note on cloud cover, I do not go shooting in-flights on days that are completely overcast as that drops my shutter speed down too low to get good shots. In fact I prefer completely sunny days as even occasional clouds can complicate things as you will see in the next setting.

My final setting is totally manual, ISO 400, shutter speed 1/1000 and f5.6. I use this in places where I am shooting against water with lots of reflections or against vegetation that is not a uniform shade. As long as it remains sunny the whole time this usually works fine. The sun going in and out behind clouds can complicate things and then I dial the shutter speed down and back up as needed.

One of the biggest challenges is getting the dragonfly in focus. Some cameras have a feature called auto focus with manual override. This allows you to manually focus on your subject and when you are close you hit the shutter and the camera fine tunes the focus before taking the picture. It isn’t perfect, but it a lot better than what my Panasonic has which is straight auto focus. I find that the best way to lock onto the subject is to have the camera focused just this side of the dragonfly. If the camera is focused the other side of the dragonfly then it searches out and often locks on the background. If it is focused too much on this side of the subject then as it searches out it often just goes right past the subject. So I try to guess where the dragonfly is likely to appear and pre focus on something that is slightly closer to me. This is not as difficult as it may seem because if you watch the behavior of dragonflies they often follow the same flight pattern.

Be prepared for a long session though. If you think that you can go out for an hour and come back with several good photos, you are probably going to be disappointed. I will give you one good hint though, if you live in western North America and are familiar with the Paddle-tailed Darner. That is the most cooperative darner I know of. It will often hover for quite long periods of time and quite close to the photographer, in fact sometimes too close to focus on. Here is a photo to prove it.

Common Green Darners on the other hand usually hover for very brief periods of time and are much more difficult to photograph, and some darners like the California do not hover at all, at least not that I have seen.

Many other species of darners hover at least occasionally, as do a few other groups of dragonflies. You will have to learn which ones are likely to do so in your area. Then there are all the species that only hover under very specific circumstances. In many species of dragonflies, like the Four-spotted Skimmer, the male will hover over the female when she is ovipositing, and this may be the only time you will catch him hovering.

Females of some species like Common Whitetails will often hover briefly when ovipositing into the water.

Some species like the Cardinal Meadowhawk that lay eggs while flying in tandem will hover while doing so.

If you are not that familiar with the dragonflies in your area you might want to talk to a local entomologist who is, as he or she might be able to suggest what species occur in your area, where they occur and perhaps even which species might be the easiest to photograph. One thing is for certain, the more time you spend photographing dragonflies the more you will learn about these fascinating creatures and the better your photographs will become.

Vancouver Island Dragonflies, 2012 season – Terry Thormin

It has turned cool here, cooler and cloudier than normal, and it feels like fall. Dragonfly populations are noticeably on the decline and many species have disappeared altogether. So I have decided that it is time to wrap up the season with a blog.

This year was a mixture of good and bad when it comes to dragonflies, and I will give you the good first. I managed to see five new species for the island and I managed to photograph four new species and get a few species in flight that I had struggled with before.

Forty-one species of dragonflies have been recorded for Vancouver Island, and my hope is to eventually see and photograph all of them. The main reason that I did so well this year is that I finally found a bog at higher elevation. The bog is part way up the road to Mt. Washington at an elevation of 2620 feet, and is aptly named 9 km Bog. Here, with the help of two good friends who are as crazy as I am about dragonflies, we managed to find Hudsonian Whiteface, Crimson-ringed Whiteface, Sedge Darner and Ringed Emerald and all four were new for us on the island. It was easy for us to photograph the Whitefaces as they regularly perched on the vegetation, but the darner was more of a challenge as we had to get it in flight, but all three of us succeeded. The emerald was the tough one as it rarely hovered for more than a couple of seconds and was very hard to find perched. This one I did not get although I have a perched shot from Alberta.

On one of my trips to Bowser Bog, a bog at low elevations that has recorded 26 species of dragonflies, I finally managed to get photographs of a perched Saffron-winged Meadowhawk. Of course, a few days later I photographed one in flight at Little River Pond. This was the first record for that species at Little River Pond, putting the total for the pond up to 21 species.

My final good dragonfly was a Black Saddlebags at Rascals Pond in Parksville. Black Saddlebags is a dragonfly that is recorded only sporadically for Vancouver Island. I do not have all the records, but I know that it has been a few years since one has been seen on the island. This is a known migrant, and it is probable that our records are all of migrants from the south. Considering how few active dragonfly watchers there are here, this species could be much more common than the records indicate. There were at least three individuals at Rascals Pond, two males and a female that I observed ovipositing. As well there was at least one other individual at another pond in Parksville. I went to Rascals Ponds three times and saw the Black Saddlebags on all three occasions, but because they were always in flight I was unsuccessful in getting any photographs.

As for those in-flight shots, I mentioned two of them, the Blue Dasher and the Four-spotted Skimmer, in an earlier blog, “Photographing Dragonflies In Flight”, but at that time I had not succeeded in getting a good in-flight shot of a Common Green Darner. Well I finally did and, as is so often the case, I have since then managed to get a few more good shots. So here is one of them.

And to top it off, I also managed to get my first in-flight shot of a Striped Meadowhawk, another species I had tried for without success on previous occasions.

I have managed to see 26 species of dragonflies so far this year, and succeeded in getting lots of photographs, so what is the downside? The answer can be summed up in one word, numbers. The darners in general seem to be down in numbers somewhat, although not dramatically. The skimmers and meadowhawks though seem to be drastically down, at least in locations that I am familiar with. Meadowhawks that we were seeing in large numbers at Bowser Bog last year we were only getting ones and twos of this year. The numbers of Common Whitetails, Four-spotted Skimmers and Eight-spotted Skimmers at Little River Pond seemed to be down this year and I saw very few Dot-tailed Whitefaces and not a single Western Pondhawk. The meadowhawks in general were well down in numbers. In fact, the Autumn Meadowhawk, which is our last dragonfly to appear, generally emerging in numbers in mid August, has not put in an appearance this year at all so far. I spent two hours at Little River Pond today where it is usually common by now, and although I did see five other species of dragonflies, there was not a single Autumn Meadowhawk to be seen.Just so you know what this dragonfly looks like, here is a photo of an Autumn Meadowhawk taken last year.

The only dragonfly that I can say has been truly here in good numbers is the Common Green Darner. In fact I don’t recall them being this numerous at Little River Pond before. The interesting thing though is that, like the Black Saddlebags, this is a migratory dragonfly. It would be hard, maybe impossible, to determine what percentage of our population is made up of migratory individuals, as there is a resident population as well, but it is quite likely that the large numbers of this species this year are accounted for mostly by migrants.

I have been concerned about insect populations on the island ever since I moved here three years ago, and other people who have lived here much longer than I have expressed the same concern. But dragonfly populations seemed to be the exception, that is, until this year. Because dragonfly larvae can live for several years before emerging as adults, this might just be the reason why they were not showing a population decline until now. It is interesting that the meadowhawks are showing the biggest decline in numbers, and these are the smaller dragonflies and the ones that generally spend the least amount of time in the larval stage. This decline in dragonfly numbers is very worrisome, and it will be interesting to see if it continues next year. I believe that this island needs a wakeup call, but I am not sure what it will take to do it. Unfortunately most people pay so little attention to insects that they will never notice declines in populations, and if they do I am not sure they will recognize the significance.

When I wrote an earlier blog “A Passion For Dragonflies” I included a poem. When I wrote that poem, in a frenzy of creativity I wrote another, free verse version of the poem, which I did not include with the blog. Somehow that poem seems appropriate now, so here it is.

Dragonfly

It courses over the pond

on wings flashing in the sun.

Colours of red, blue, green and yellow,

colours of the rainbow,

and black and white for contrast.

It hunts for food,

for a mate,

for the next generation.

Always keeping an eye out for danger,

from above and below.

But the real danger it does not see,

the danger from humans.

draining wetlands,

using pesticides,

herbicides.

A danger that kills all,

indiscriminately.

But its loss is our gain.

Or is it?

For if we lose the dragonflies

do we not lose part of our humanity?

Part of our souls?

Part of the soul of our planet?

Is it not better to protect the dragonflies?

To watch, to really see them?

They can bring joy,

peace,

tranquility.

If only we all could become

“Watchers at the pond”.

© Terry Thormin, August 2012.

Hunters in the Pond Part 2 – Terry Thormin

The dragonfly patrols the south shore of the pond, searching for a mate. It is the largest of the dragonflies in the pond, a Common Green Darner, and so pays little attention to the other dragonflies even when the diminutive Blue Dasher comes darting out at it in an effort to protect its territory. From the top of a pine tree at the east end of the pond a Merlin surveys the pond, waiting for the right moment. There are several Common Green Darners flying and surely one will be careless this time. Now! It launches itself from the pine and plummets down, picking up speed until it levels out low over the water. Distracted by the dasher, the darner doesn’t see the Merlin until it is almost too late. Frantically it twists and picks up speed, but the Merlin is too close and rakes its left side, almost tearing both wings off. The Merlin continues down the pond without its prey, but the darner, badly injured, spirals to the water’s surface where it flaps in a futile effort to take flight.

The rippling water sends out a circle of vibrations and very quickly a water strider responds, skating across the water’s surface towards the injured dragonfly. It approaches and when the struggles subside it moves in. The initial jab from its needle-like mouthparts starts the dragonfly struggling again and the strider quickly backs away. A few minutes later the struggles quiet down again as the life energies seep from the body of the dragonfly. Again the strider moves in and pierces the dragonfly’s body with its mouthparts. Now the dragonfly is only struggling weakly and the strider persists, sending digestive enzymes into the dragonfly and sucking up the resulting dissolved fluids. Within a few minutes there are four striders feeding on the dragonfly, then five and finally six. Two species share the dragonfly carcass. There are three larger water striders, wingless even as adults, and three smaller ones, all with wings. Within a couple of hours the water striders have abandoned the darner’s body and there is little left but an empty husk. Even then a couple of snails move in, gleaning whatever is left. Nothing goes to waste in the pond.

I did not actually observe this event, it is fictional, but one that could easily happen. I have observed water striders feeding on other insects trapped on the surface of the water, and just recently photographed a group of water striders feeding on a dragonfly, in this case a Hudsonian Whiteface.

Water striders are both predators and scavengers, feeding on any insect that falls onto the surface of the water. They are also known as pond skaters and Jesus bugs because of their ability to walk on the surface of the water. They are found on quiet water like marshy lake edges ponds, marshes and backwaters of rivers and creeks. They do not like fast flowing water. There is one exception to this though, and quite a remarkable exception. Water striders in the genus Halobates are the most marine of all insects. While most of the 46 species in this genus are found in coastal areas, 7 species are truly marine in distribution and can be found hundreds of miles from any land. Unlike other members of the genus, and other water striders, these 7 species feed on plankton.

Water striders are true bugs and as such they do not go through complete metamorphosis. Instead the young water striders look very similar to the adults, just smaller and without wings. The young, like the adults, live strictly on the surface of the water. There are about 750 species worldwide, the largest getting up to more than 36 mm in length.

There is another pond insect that deserves attention, the water scorpion. It is not a true scorpion, but rather an insect, and is a true bug just like the water strider. Unlike the water strider though, it spends most of its time below the surface of the water. It is an air breather though, and has to come to the surface to breath. Water Scorpions, however, have breathing tubes at the back end that are often almost as long as the body. For this reason they are often found sitting on vegetation below the surface with just the tip of the breathing tube sticking out of the water.

Water scorpions are ambush predators that look like aquatic walking sticks, but with front legs that look more like those of a praying mantis. Some species though are much broader through the body and look something like a skinny giant water bug.

Earlier this summer I observed a rather interesting episode with a pair of damselflies and a water scorpion. As usual I was sitting in my camp chair beside Little River Pond waiting for opportunities to photograph dragonflies when I noticed some activity in the water right at my feet. It was a female damselfly below the surface of the water. Female damselflies will often go completely underwater to lay eggs and the theory is that by so doing they will not be harassed by other males attempting to mate with them. Usually they remain attached to the male they mated with, but on this occasion she was by herself and she seemed to be struggling to climb to the surface on an emergent plant stem. I looked more carefully and noticed a water scorpion that had grabbed her by the wings. Most likely while she was ovipositing she got too close to the water scorpion which made a grab for her and only got the wings.

With great effort she managed to drag herself partly out of the water. Then a male flew in, most likely the one she had mated with, and grabbed her with his appendages by the front of the thorax. Anyone who is familiar with dragonflies and damselflies will recognize this as the tandem position. Between the two of them they managed to eventually drag the water scorpion completely out of the water. Shortly after the female was clear of the water the water scorpion dropped back into the water, either having let go or perhaps tearing through the wings of the female damselflies, and the damselflies flew away. That the male came to “help” her I seriously doubt, but my guess is that the female would not have made it without his help.

Water scorpions range in size up to about 44 mm not including the breathing tube. There are about 270 species distributed worldwide. All are ambush predators and will feed on things up to the size of tadpoles and small fish. They are found in quiet, shallow lakeshores, ponds and slow moving streams.

There are many other predators found in ponds, marshes, lakes, streams and other freshwater habitats, and perhaps at sometime in the future I will write about some of them. Anyone who takes time to sit, and observe at the edge of a pond will undoubtedly see and learn something about many of these fascinating creatures. Unfortunately, most of us leave our fascination with pond life behind when we reach out teens. I think that this is unfortunate as it is an amazing habitat with many amazing creatures, and one that is a good indicator of the health of the planet.

An Outdoor Dragonfly Workshop – Terry Thormin

This past Saturday I conducted an outdoor dragonfly workshop for the Comox Valley Naturalists Society. The event was advertised to the general public as well and about 25 people attended, including five children. For the middle of the summer this is a pretty decent attendance. The event took place at Little River Nature Park where there is a pond that supports a good population of dragonflies. In an earlier blog I mentioned that I had recorded a total of 18 species at the pond, but when I recounted recently I came up with 20 species. For such a small pond on Vancouver Island this is a very good diversity.

Of course a number of those species have been seen only rarely and even amongst the more common ones you can’t expect to see all of them on any one day. So when we got a total of 8 species this day I figured that the day was a success. More importantly we observed lots of behavior which gave me lots to talk about. The Common Green Darners were laying eggs in the stems of the water shield, and the Cardinal Meadowhawks were flying in tandem, dropping their eggs one at a time directly in the water. The diminutive Blue Dasher would perch on a blade of grass and then suddenly dart out to give chase to a much larger Blue-eyed Darner. Canada Darners hovered close to shore giving the photographers opportunities to try for in-flight shots and several Striped Meadowhawks were observed hovering and perching in the grass back from shore.

The best show thought was put on by the Merlin later in the afternoon when many of the people had left. The Merlin is one of the smaller falcons and it loves to hunt dragonflies, especially the Common Green Darner. I described this behavior in my earlier blog, but will go over it briefly here for those that did not read that blog. The Merlin perches on a bare branch near the top of a large conifer at the east end of the pond. When an opportunity arises it will launch itself from the tree and come barreling down the pond in pursuit of one of the darners. If it is successful it will fly back to the tree to devour its prey.

On one occasion this day, just after one of the photographers had taken some photos of a pair of Common Green Darners close to shore in the process of laying eggs, the Merlin swooped in and with outreached talons plucked the pair off the lily pad right in front of us. I have observed the Merlin going after darners in flight many times, but this is the first time I saw it take a pair of ovipositing darners. I now suspect that this must be the preferred prey for the Merlin. After all, ovipositing darners are like sitting ducks and you get two for one and I am sure even Merlins appreciate twofers.

I believe that Little River Pond is a good barometer for what is happening to dragonfly populations in this area and perhaps on the whole of Vancouver Island as well. Unfortunately, most dragonflies seem to be down in numbers and some species have been totally absent from the pond. The only species that seems to be doing well is the Common Green Darner, and this is a migratory species, so our resident population may have been augmented by migrants from the south.

As Annie has pointed out many times, butterfly populations on the island are way down, and my observations lead me to believe that other insect populations are suffering as well. It is hard to determine what the cause is, and it is highly unlikely that it is only one cause. I do know that without insects we simply would not survive. They pollinate about 80% of all flowering plants and are the source of food for most birds. What doesn’t eat insects eats those things that eat insects or eats the plants that insects pollinate. Our education system is failing badly when it comes to providing students with a proper insight into the importance of insects in the environment.

A recent report from North American Bird Conservation Initiative states that aerial insectivores in Canada are declining faster than any other group of birds, and the Barn Swallow and Chimney Swift are down to about a quarter of their 1970 population levels. It also states that on the pacific coast, where human settlement, forestry and industry are most intense bird populations overall have declined by 35%. Although this cannot all be attributed to a decline in insect populations, there is no doubt that this is a major factor, and if you consider loss of habitat as one of the factors in bird declines, you have to remember that loss of habitat also means a loss of the insects that inhabit that habitat.

I had not intended this to be anything but a report on the success of a dragonfly workshop, but somehow I managed to get sidetracked into talking about what we are doing to the environment. These conversations seem to occur quite regularly and I am convinced that, amongst my circle of friends at least, most people are becoming more and more concerned. Annie and I are trying through these articles to make people more aware of what is happening on Vancouver Island and elsewhere. It seems like a small thing at times, and we wonder if what we are doing will have any impact at all, after all it is big business and the government that need to change. But almost all big change starts from small beginnings, and we can only hope.

Pining for the Pine White Butterfly – Annie Pang

“Look who has come now, all trimmed in black lace,

riding down on a breeze right up to my face!

A slow drifting snowflake in late summer’s light,

floating down from the firs is the dancing Pine White…”

A.P.

How I wait for and welcome this beautiful and once plentiful butterfly that appears sometime between mid-July to early August, depending on the weather. This year, it has been a bit later as most other species have been, if seen at all but now has finally come out, along with the Woodland Skipper. The European Skipper is gone and so are the swallows where these little butterflies were. It was hard to see the swallows vanish from areas where they were once so abundant. Something is very, very wrong and even laypeople are seeing it…..well the ones I talk to anyhow. There aren’t enough insects to support our swallows and other insect-eating migratory and resident birds.

Getting back to the Pine White butterfly, it is easily one of the prettiest butterflies we get locally, and not only to my eye. Maybe it is because I have to work so hard to find them where shots can be taken at fairly close range with my camera, for they often will not come down from their lofty homes, especially the females, or if/when they do I’m not there when it happens!

The first day this year that I did manage to photograph a Pine White was up on Observatory Hill, but before this I must rewind to July 30th, the day before, when we went to Beaver Lake Ponds as this was where I got my first clues for this year that the Pine Whites were out. It is also one place I feel well worth mentioning on its own.

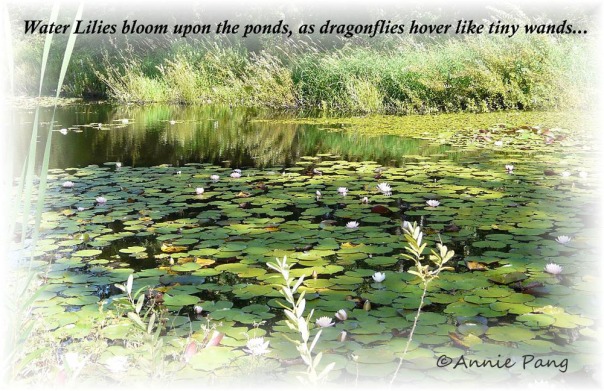

Earlier in the spring, I’d been to the Ponds a few times, but the place had been so badly flooded from all the rain we’d had that access to the area where I’d hoped to find the Four-spotted Skimmer was cut off. This time, however, after months without much rain I was certain I could get through the narrowed path enclosed by a zigzag wooden fence, probably put there to keep out motorcycles and bikes. I could see the lovely man-made ponds that were running wild with water lilies and were now habitat for a number of indigenous creatures. This place had always been, for me, a place of solace and refuge.

But access to the ponds as I’d known them in previous years was still flooded and I had to walk around the long way, where horses, cyclists, joggers and folks walking their dogs had a proper trail adjacent to private properties. I was surprised and disappointed until something white came zipping up from the trail suddenly flying out and up, right into my face and then … it disappeared. We looked up and searched the trees and we saw them. Like bits of floating tissue amongst the firs, there was no comparing them to the skittish flight pattern of the Cabbage Whites. Seeing Pine Whites in flight was, to my eye, more poetic and reflective of the lazy summer days.

The Pine White butterfly spends most of its life cycle high up in the world of hemlock (where hemlock can be found these days?), pines and Douglas firs. Overwintering as an egg the caterpillars feed in spring on the new growth of needles. The adult emerges from its chrysalis later in the summer to mate and females lay their eggs up in the treetops, with both sexes only coming down to nectar on flowers. But aside from the one that I startled on some nearby Oceanspray that looked a bit past its “Best Before” date, they would not come down that day where I was as there were no other flowers along the trail in the sun to tempt them.

While we were there however, I decided to check out the ponds from this side. We turned off the main trail onto a path leading towards the ponds and it was here I spotted a few different dragonflies that posed beautifully for some decent shots which I simply couldn’t pass up. I managed to get both a male and a female 8-spotted Skimmer, the male being immature, as a mature male develops a powdery white coating (known as “Pruinescence”) that covers the abdomen and this one had not as yet. But it did have the claspers of a male plus the white patches and black “spots” on its wings. The female’s wings were typical of the species; clear other than the 8 “spots” of black on the wings.

The next dragonflies we encountered were a few Paddletail Darners but I did not manage any shots of them as I find I’m just not quick enough or patient enough these days with time so constrained and my reflexes a bit too slow. As well, the area we’d normally spent time trying to get them in flight even on this side was still flooded by….. maybe a beaver, and access to the narrowed pathway with the wooden fenceway was still flooded on this far side as well, although I could see the path itself, mucky and a bit forlorn-looking, being cut off by water.

But I did luck out in finding a Striped Meadowhawk. I really enjoy the Meadowhawks as they are “perchers” and easy to get decent pictures of but I’ve never managed to get one in flight as Terry managed to do with his Blue Dasher and Four-spotted Skimmer, all of them being “perchers” rather than “cruisers” like the Darners.

Although the dragonflies were a balm to my growing frustration with this elusive butterfly, I wasn’t ready to give up on the Pine White and this is what found us driving up “Little Saanich Mountain”, also known as “Observatory Hill” (this is where the Observatories are), the next day. A friend of mine had found and photographed a male Pine White here last year some days after I’d found my first one in a different locale, so I was optimistically reserved.

At first, as we arrived, we found a few drifting from treetop to treetop but nothing to see at ground level. We had parked in the same area I’d come out and photographed the Pine White the year before after my friend had told me about it, at the base of the top clearing, where the first buildings are. Discouraged again that there was nothing at ground level, I told John to drive the van slowly up further as I kept walking and searching. A few minutes later, John pulled up by me and, in an excited voice, told me that one had come down to nectar. We drove back down and I saw nothing at first, and then – there he was!

I say “he” because the males and females differ quite a bit in appearance. This male gave me a generous amount of time before leaving. When I looked at the pictures later, I saw he was damaged but I was happy enough to find one, even if the birds may have gotten to him first.

But I was determined to continue my search. The following day, we set out to cover three different locations. The first was Esquimalt Gorge Park where I knew for certain that there was Goldenrod (Solidago sp.) coming into bloom, but despite this I found no sign of Pine Whites in the decreasing number of firs in the park. Once these lands were filled with old growth forests, but with clearing the land of more and more trees, the Pine Whites had less and less habitat in this area and with less habitat, any woodpeckers and Pine White populations weakened second and third growth firs so that winter and spring windstorms easily brought down yet more treetops or entire trees.

Our next stop was “The Garden Path”, a private garden owned by Carolyn Herriot and Guy Dauncey, both conservationalists. There we saw a few Pine Whites up in fir treetops again, and again, not coming down. With a sigh I figured it was time to check out Glendale Gardens before giving up.

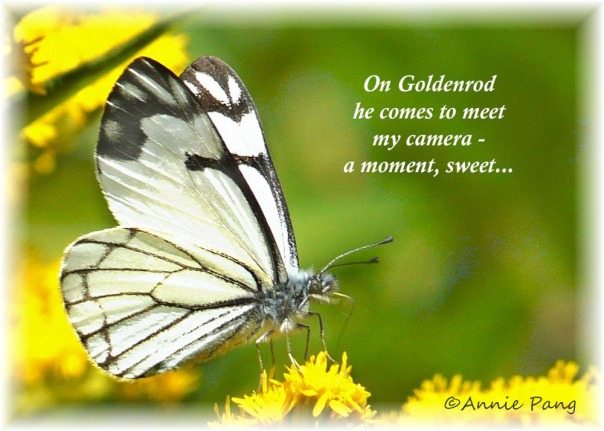

We arrived in short time and this time I struck gold…….or Goldenrod in full bloom in the garden entrance. And there were Pine Whites in Douglas firs across the street!! One was flying lower and lower and…..it finally alighted on the Goldenrod to feast…..right smack on the fence side where I could not possibly get to it without creeping like some sort of criminal through the neatly mulched flower garden. But such was my growing frustration that I decided desperate times called for desperate measures. I told John to watch for anyone looking, and I gingerly stepped in behind and out of sight snapping longshots of the nectaring butterfly as I crept closer and closer. What madness to be sneaking about like this to get shots of a solitary butterfly where there used to be so many!! Did I feel guilty? Not a bit! It was another male and though he jumped about a bit, he kept returning and I was allowed to get so close at times, I had to pull my zoom lens in. People walked by but didn’t seem to notice or care, including some staff. I was not a new sight to them there. This butterfly was in pristine shape and I wanted as many good shots as I could get!

And so, third time lucky, though hot, sweaty and tired, we checked in with the office so I could make my “confession” while showing the pictures I’d gotten. All I got were smiles, a few “oo’s and ahh’s”, a very good thing, and then we were off home. But this year I have seen no females at ground level and although I have photographed males every year since I began photography, I’ve only managed to find a female twice in all this time.

According to butterfly expert, Cris Guppy, whom I’ve had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with, I quote from a recent email exchange with his permission regarding this butterfly we both seem to be quite fond of:

“There are records from the early 1900s of huge outbreaks of Pine Whites that resulted in drifts of them washing up along the top of beaches. The last outbreak in BC that I know of was in Cathedral Grove west of Parksville in the early 1960s, which the Forest Service sprayed insecticide on. I was a kid with my family driving through there, with “snowdrifts” of bodies along the side of the highway. I suspect that they require large areas of old growth hemlock and Douglas fir forest to build up huge populations, and logging put an end to both the old forests and the huge populations of Pine Whites.” – Cris Guppy

With the major upheaval that occurred at Esquimalt Gorge Park while putting in the new Japanese Garden, this is the first year I have found no Pine Whites in their main garden area nearby. I count this now as two butterfly populations eradicated in this park due to habitat disruption or destruction.

Before closing with this sonnet and a file picture of a female Pine White, I’d like to wager that as soon as this blog is posted, I may well find and photograph a female. If that does happen, I’ll post it with a very brief (I promise) poem and comment!

Song to a Pine White Butterfly

Dear butterfly, so beautiful and fair,

what have we done to make you hard to find?

Cut down so many trees without a care

and poisoned you for living! Oh how blind

and greedy has the human race become.

So now I struggle just to find a few

and if I search enough I may find some.

How lucky I feel now that I found you.

But where is your sweet lady? Does she fly

high up beyond my reach where I can’t see?

High up, too high up for this sorrowed eye,

it makes me ponder how this came to be.

Some day I hope that we will meet again,

beyond this place where greed brings only pain…

© Annie Pang August 7, 2012.